About two years ago, I read a string of books that were all published in 1965. It was a fun exercise and I found some wonderful books I might not have otherwise read (described in this post). Why not repeat this for a different year? I picked 1937. In part, I wanted something more distant than 1965. In part, I thought our current president’s dictatorial aspirations and megalomania might have echoes in books of that period. The twelve books I read, mixtures of fiction (9), non-fiction (3), and audiobooks (3); famous and obscure; good, bad, and bizarre:

- Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston. Fiction.

- Thieves Like Us by Edward Anderson. Fiction; Audiobook

- Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb. Fiction.

- The Bachelor of Arts by R. K. Narayan. Fiction.

- Museum by James L. Phelan. Fiction.

- The Blind Owl by Sadegh Hedayat. Fiction.

- Jordanstown by Josephine Johnson. Fiction.

- Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck. Fiction.

- I, Yahweh: A Novel in the Form of an Autobiography by Robert Munson Grey. Fiction.

- The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell. Non-fiction; Audiobook.

- The Road to Oxiana by Robert Byron. Non-fiction; Audiobook.

- The Life and Death of a Spanish Town by Elliot Paul. Non-fiction.

My first realization when starting the journey into 1937 was that it was hard to find books. There were fewer books published in 1937 than in 1965 or in 2025! I don’t have exact numbers, but searching the University of Oregon library catalog for 1937 fiction available as print books in English gave only 325 titles. For 1965, it’s 674; for 2016, it’s 1146. (For 1516 to 2025, it’s 78016.) One can also get a sense of the sparsity from the Wikipedia page on 1937 in literature. At first glance, books to read seem plentiful enough — there are 87 fiction and 13 non-fiction books. But looking more carefully at this or the library catalog, a sizeable fraction are mystery novels, which I wasn’t keen on reading. I also omitted a few books I’ve read before, such as The Hobbit, though my final list does contain one book I intentionally re-read (Of Mice and Men) and one that I forgot that I had already read (The Road to Oxiana)!

Favorites

The two books I thought were truly excellent were Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, a Hungarian modernist novel I had never heard of, in which the main character leaves his wife during their honeymoon in Italy, is haunted by characters from his past, and questions his life. This sounds like it could be awful, dull modernist navel-gazing, but it’s clever and often very funny, with a host of fleshed-out, interesting characters. Coincidentally, this year’s Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to another Hungarian, László Krasznahorkai.

The other excellent book I had heard of, and everyone knows the author: The Road to Wigan Pier by George Orwell. The first half is a fascinating account of spending time with miners and other poor, working class people in Northern England, documenting the stunning difficulty of their lives. The chapter on mining is chilling. The second half is very different — a critique of British socialists, mainly lamenting their inability to connect with their skeptics rather than preaching to the choir of vegetarians and sandal-wearers. (As a vegetarian sandal-wearer I found this amusing.) The book was a selection of the Socialist “Left Book Club” in 1937. At first, I didn’t like the second half, but then it grew on me, and many of its critiques seemed eerily applicable to present-day politics.

Also very good: Their Eyes Were Watching God, a well-known and very poetic classic I hadn’t read, about a black woman in 1930s Florida and her three marriages; Thieves Like Us, unsentimental portraits of criminals driven both by desperation and by a lack of a sense of moral responsibility; The Bachelor of Arts, about a student finishing college in South India and trying to figure out what to do with himself; and Of Mice and Men, which is beautiful, but which doesn’t quite make it to the favorites list because it’s a bit too precisely structured.

Duds

My journey to 1937 involved a greater number of mediocre books than I usually read. Some are obscure, but some are not. The Blind Owl is, apparently a classic of modern Iranian literature, but I fail to see why. It’s a surreal, nightmarish short novel that starts off captivating, but becomes monotonous and unrewarding.

Museum is one I unearthed from the university library catalog with no prior knowledge, as was Jordanstown. In both cases, I suspect I’m the first person to have held these books in many decades. Both have a clear goal of social criticism. Museum is a look at prison life and its effects on the mind of the narrator, who over the course of about 15 years goes from articulate and naïve to bestial and cynical. Unfortunately, it’s not interesting enough to recommend. Too much of it is hard to follow, in part due to occasional stream-of-consciousness impressions. I expected to find more of this in 1937 than I did — novels trying too hard to be modernist “art.” It’s also too long. Mine is currently the only review of the book on Goodreads. A review I dug up from Time magazine in 1937 ends with the biting note, “Although readers will be impressed by the authenticity of his story, they are apt to finish it with something of the same relief they might feel at getting out of jail themselves.”

Jordanstown tells of a contemporary Depression-era town, home to the well-off and to a larger number of the poor and struggling. It gives a mildly interesting glimpse into the period, but it provides neither deep insights nor good entertainment. A contemporary New York Times review writes about the story: “Summarized thus, ‘Jordanstown’ no doubt sounds like a dozen other novels.” As such, it’s probably a representative novel of the year! Mine is one of two reviews on Goodreads.

The Life and Death of a Spanish Town is the book most relevant to the themes of war and fascism. It’s a reminiscence and a catalog, describing nearly everyone living in small village on the Spanish island of Ibiza in 1936, at the start of the Spanish civil war. The English author lived in the town and was very fond of it, and with this book hoped to document the place and the people who would later be destroyed, dispersed, or at least severely disturbed by the war. He describes the characters of the villagers, their interactions, and the rhythms of a place he, accurately or not, views as idyllic. I’m glad this book exists, though I also wish it were better. Unfortunately, it is quite boring. Also, though pre-war Ibiza does seem pleasant, low-stress, and beautiful, I am skeptical that it was Eden its author depicts.

The strangest stories

The strangest book of the lot, and one of the strangest books I’ve ever read, is I, Yahweh: A Novel in the Form of an Autobiography by Robert Munson Grey. This was a random pick as I wandered through the University of Oregon library stacks and looking for books with “1937” on the spine (lower right end in the photo; one of two copies):

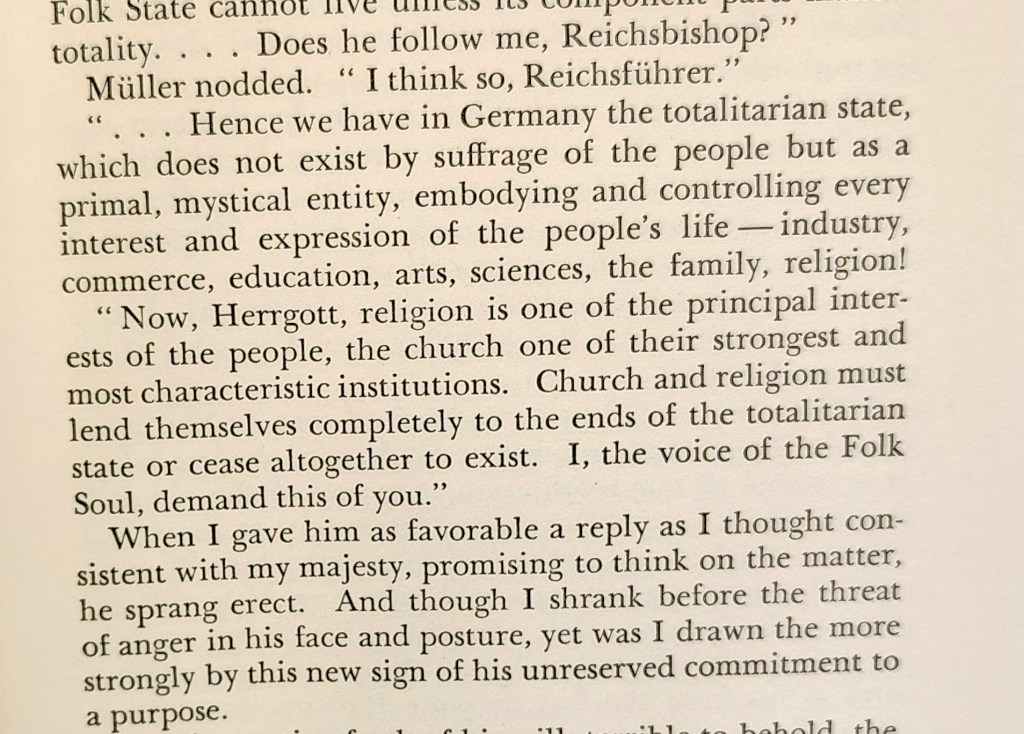

Like the title says, it’s narrated by Yahweh, the Judeo-Christian god, who recounts events of the past few thousand years – helping Moses in the desert, discussing empire with Constantine, being puzzled by Saint Francis, chatting with Hitler, and more. The beginning is excellent, though it reminded me that my Biblical knowledge is poor. (Who is Aaron? I had to look up this and other things.) Yahweh’s goals and morality are rather amorphous. Roughly around Jesus’ time the novel falls apart – suddenly, there’s a “real” capital-G God, whose relationship to Yahweh is vague. From this point on, Yahweh wanders around Western Europe and the United States, but seems stunningly incurious about the rest of the world, reflecting more the preferences of the author than anything sensible for a god. Throughout the book, Yahweh’s abilities and limitations are frustratingly unclear. The ability of some regular humans to routinely talk to Yahweh makes less and less sense until, near the end, we have Hitler yelling at Yahweh to support him in his aims. How can I rate this? Perhaps 1 star for quality, 5 for originality.

Thanks to JSTOR, I unearthed some contemporary reviews of I, Yahweh. These are more charitable than I expected, though perhaps the lack of reviews in venues I’ve heard of is saying something. In the Journal of Bible and Religion (link), Elmer Mould calls the book, “readable, entertaining, and thought-provoking.” In The Religious Horizon, (link) Rev. William B. Sharp proclaims it “one of the most original and important books of this generation” and also writes that …

The forest of forgotten books

… “I, Yahweh will undoubtedly cause a great deal of comment and discussion,” which it certainly did not, at least in any long-lasting sense. More than the fascists overrunning Ibiza or Depression-era drama, I was struck when reading this set of books by how most of them are forgotten. Even the excellent Journey by Moonlight is probably read each year by a handful of people outside Hungary. This is understandable; there are far too many books even for all the great ones to remain famous, and most aren’t great. Still, there are insights to be gained from even the average books, and their authors had a message they felt was important to convey. Of course, the books do still exist, ready to be read, stored either digitally or as physical objects. Electronically, we’re less limited by space and accessibility constraints, but it’s easier, I think, to ignore or forget about the existence of files on a server than shelves of physical books.

I always find it inspiring and thought-provoking to wander through the University of Oregon’s excellent main library, surrounded by aisle after aisle of bookshelves, almost overwhelmed by the sheer quantity of words. I’m sure most won’t be read this year, this decade, or possibly this century, but some will, and we can’t predict which ones. What’s more, regardless of immediate need, keeping these books on hand for an unknown future is perhaps the most important task of a university. I’d bet on the physical over the digital books as more likely to remain accessible following an apocalypse, but I’m glad that we have both — it improves the odds of something surviving! Wandering through the forest of pages, I can’t help but wonder if my own book, published in 2022, will attract the attention of a browser as far in the future from now as 1937 is in the past; we’ll have to wait until 2110 to find out.

Today’s illustration…

A bowl of Kousa dogwood berries. Last year’s painting was much better. I shouldn’t rush glass bowls.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy, October 16, 2025

Agreed on the paucity of memorable books from 1937. I guess that just about any year since 1945 has tons of memorable books.