Does homework matter, in a college gen-ed science course? I’ve been thinking more about this question over the past year or two, as AI tools are able to quickly and correctly answer nearly all questions I could pose to students (see this 2024 post, for example, or the examples below). I often teach general-education courses aimed at non-science majors that satisfy the University of Oregon’s science requirements, most frequently The Physics of Energy and the Environment and The Physics of Solar and Renewable Energies (yes, the name is redundant; I didn’t title it). I assign homework each week, exercises that I hope will be interesting and useful for learning the course’s concepts (example).

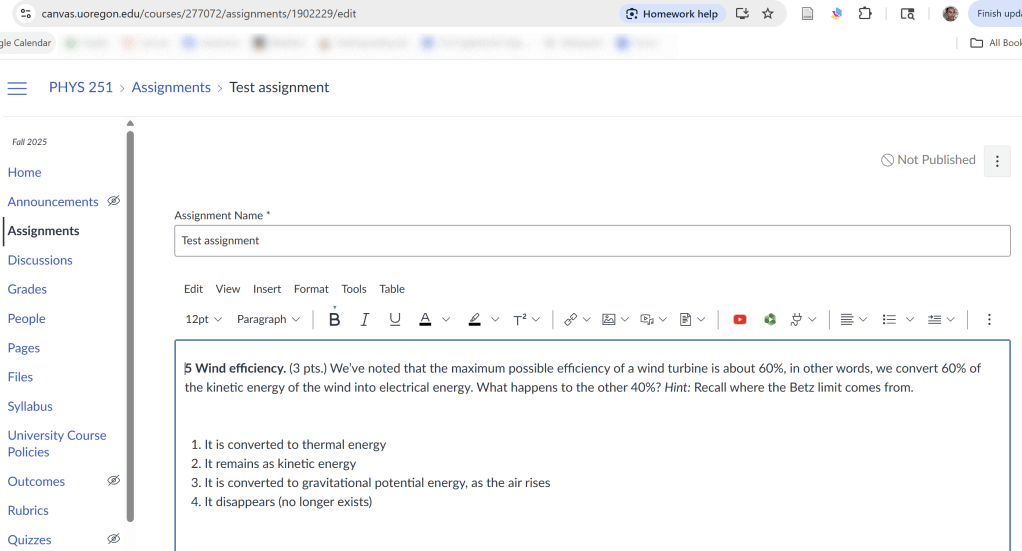

Every term I look at how the scores for each component of the course — homework, quizzes, projects, exams, etc. — correlate with each other and with the overall course grade. Last Spring, I again taught the Physics of Solar and Renewable Energies (syllabus), and the Pearson correlation coefficient between the homework scores and the overall grade excluding homework seemed especially low: r = 0.51. Is this anomalous? Is it an indicator that students can simply plug questions into AI tools, getting a correct answer regardless of whether they’ve thought through the problem? It’s true that this is easy to do nowadays, and getting ever easier. Google Chrome now automatically turns on its “homework helper” when the browser is on an educational assignment site (a Canvas page, for example), answering detected questions, in text or images, with high accuracy — I’ll give examples at the end of the post when I return to the second question. [Update, Sept. 18, 2025: Just a day after I posted this, Google removed the “homework helper” following an outcry from educators! (News story). My examples below still remain, a relic for now, but I don’t doubt some similar service will soon surface.] But first the first question, for which I have data!

I’ve taught these energy-related classes for non-science majors several times. What’s more, the overall design of the course has been quite stable. Some things, like post-class notes and mini-projects I created a few years ago (blog post) are variable, but there are always homework assignments and, with one exception, always a final exam. Moreover, unlike projects or some of the other course components, the exams are done individually, in class, and so are a direct assessment of what the student has learned. (In 2025, I don’t see how anyone can trust any exam that’s not in-person, or take any fully online course seriously. But that’s another topic…) I can therefore look at the correlation between homework score and final exam score for all the instances of this course. For Spring 2025, the most recent term, here are the individual datapoints, excluding scores of less than 25% for homework or zero on the exam which would indicate students who dropped or didn’t actually participate in the course:

The correlation coefficient is r = 0.29, and it’s clearly not a tight relationship.

Now let’s plot the correlation coefficient between homework and the final exam scores for all the times I’ve taught the course, excluding the term without a final exam. (Error bars are from bootstrap resampling.)

The most striking observation, for me at least, is that I’ve taught these courses a lot. I hadn’t realized how large the number of terms is. I enjoy these courses, and since they’re very topical the exact subject matter — graphs, news stories, data — change from year to year. But more relevant to this post:

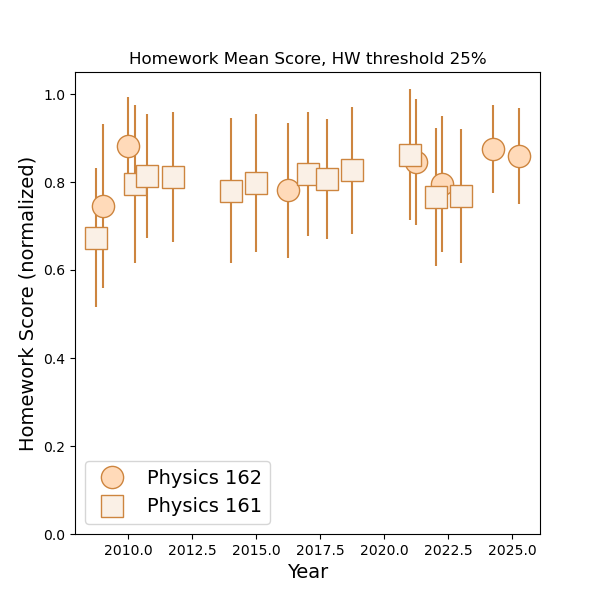

Last term’s homework correlation was lower than the average of recent years’, but not by much. The correlations have always been around 0.4 ± 0.2. There’s one outlier: Spring 2016, in which the correlation is roughly zero. I have no idea why; there was nothing unusual about the format of the course; no disasters struck; I didn’t write surreal exercises. Other than this anomaly, the data are quite boring. Perhaps the low 2025 value is the harbinger of further declines, but I can’t conclude this. The mean score on the homework assignments, again limited to scores above 25%, has been very stable:

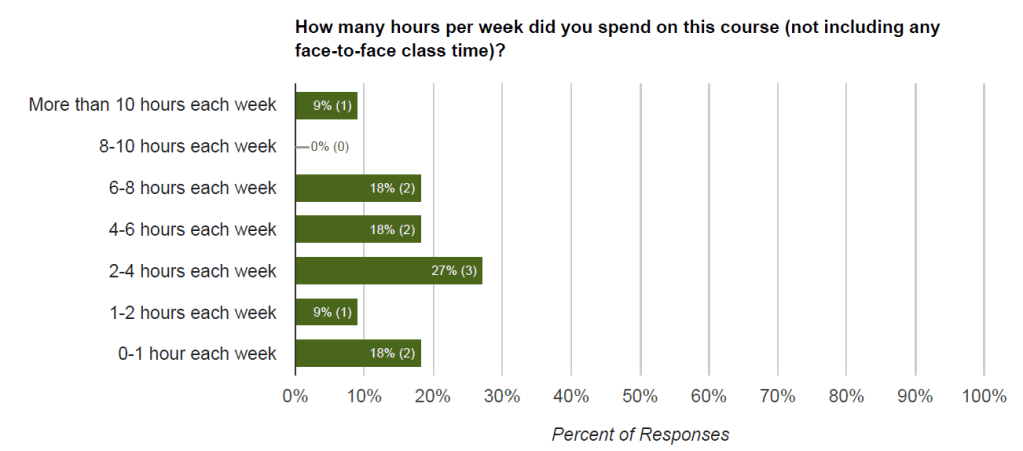

What, one might wonder, “should” correlations between homework and exam scores be? In physics, one is used to thinking of problem sets as extremely important — doing them is how most learning occurs. I recall countless hours per week, typically in one of the many libraries at Berkeley, spent thinking and scribbling, occasionally with satisfying bursts of inspiration as I figured something out. This, however, is a view of upper level courses that doesn’t much resemble the situation in gen-ed courses. First, the assignments are intended to be fairly easy, as is the course in general. Second, students have many opportunities to get assistance with the exercises — I devote an (optional) hour each week to this, in addition to my regular office hours; there’s no good reason not to be able to answer everything perfectly. The reader may find it interesting to note that, as is typical for these sorts of courses at a typical US university, students spend little time studying or doing homework for these classes. Here’s my most recent data, from the Spring 2025 end-of-term survey, which admittedly had a low response rate (20%):

The degree of correlation that does exist between homework scores and exam or overall course performance is, perhaps, largely driven by both being consequences of general conscientiousness. Simply doing the homework, regardless of the score on it, is the important measure.

What about AI?

As I’ve written before, current, free-to-use large language models can easily answer homework and exam questions from courses like mine, or more advanced courses. My wife recently told me about Google’s “Homework Helper,” or as I’ve seen it referred to elsewhere, “insta-cheat,” which automatically appears in the address bar when a Canvas site is loaded. (Canvas is a very popular “learning management” system used at the University of Oregon and countless other universities and K-12 schools. I don’t know if the “Homework Helper” works for other systems.) Clicking it, one draws a box around anything on the page, a homework question for example. Google Lens parses the snapshot, and Google’s AI returns the answer. How well does it work? Let’s see…

It takes a few seconds to click and draw a box; Google’s answer is correct:

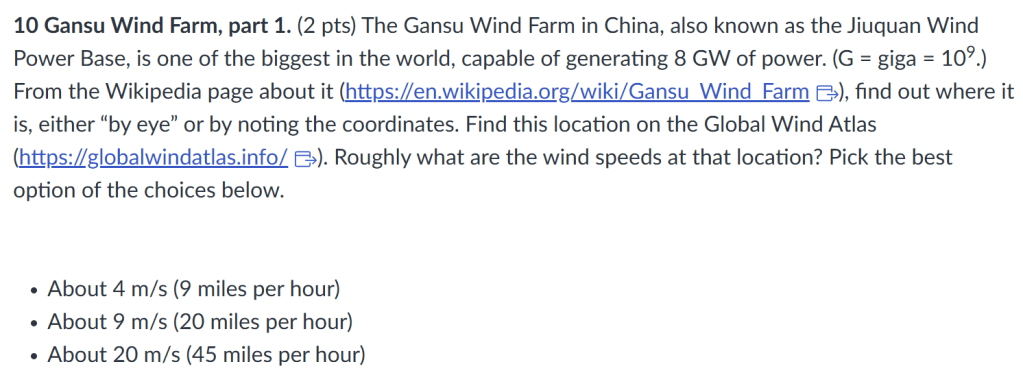

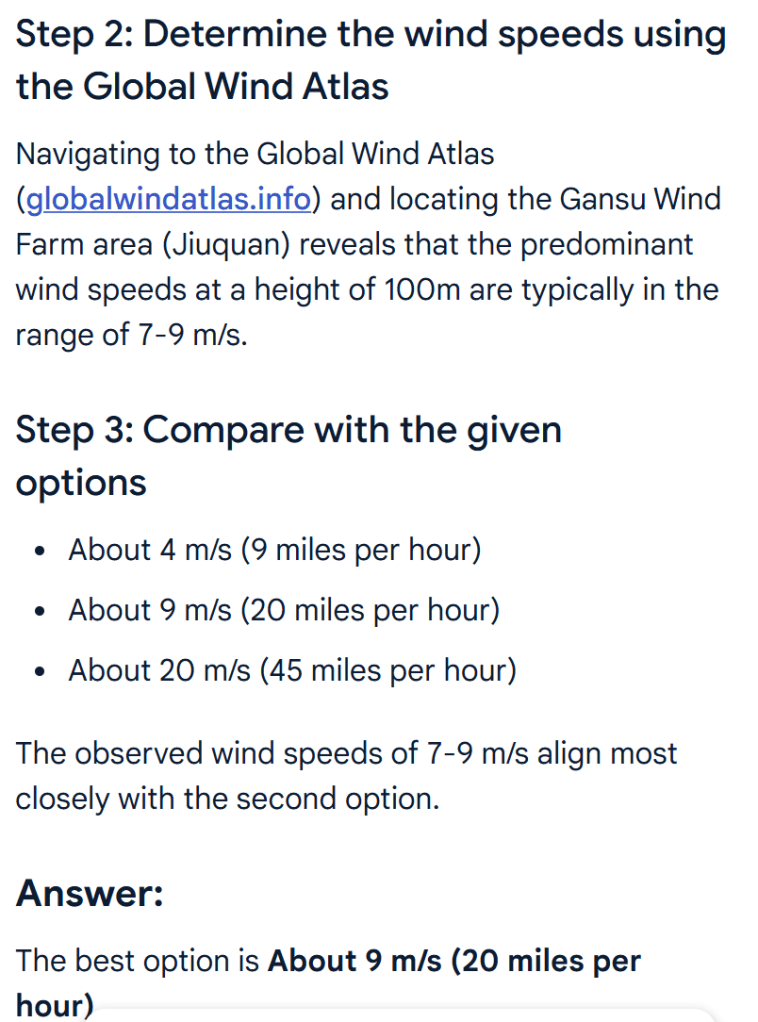

It can navigate web pages:

Answer:

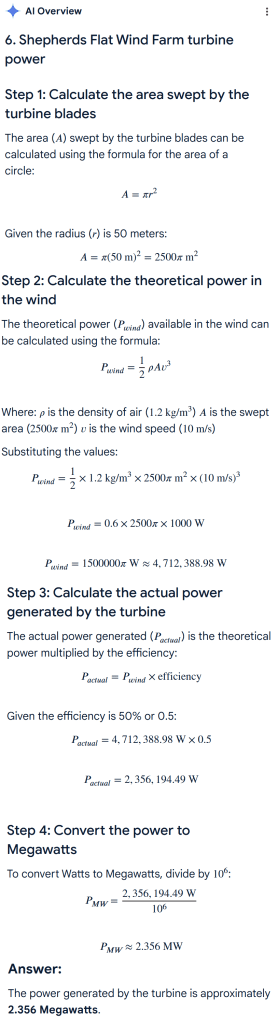

Here’s one with numbers:

Again, the answer is perfect and nearly instantaneous:

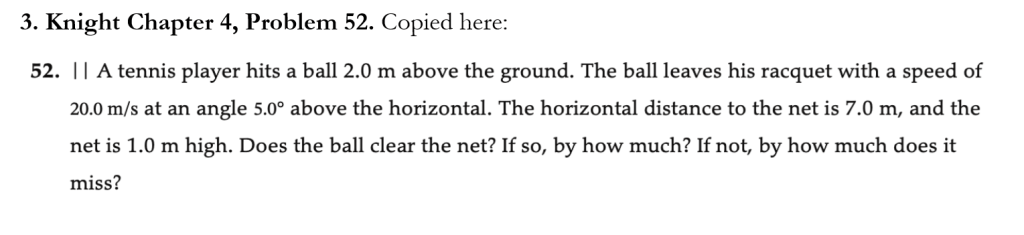

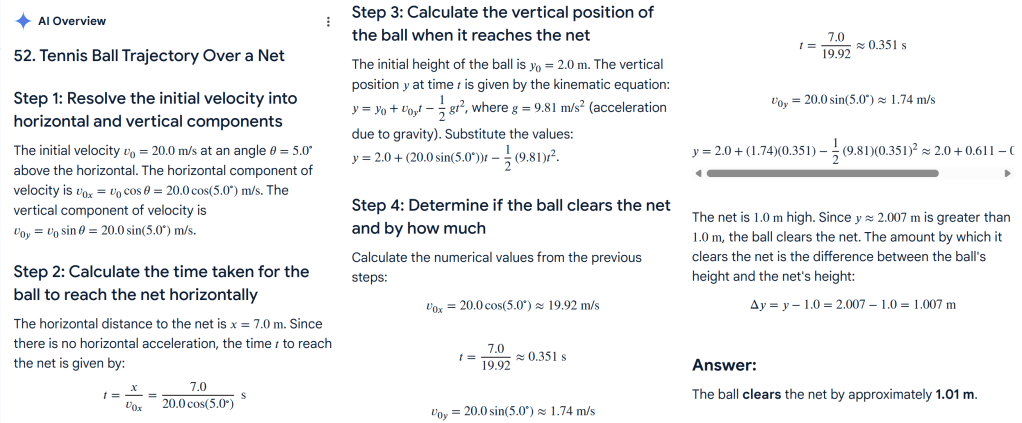

Here’s a question from a different course, our first term physics with calculate for science majors (Physics 251, for local readers), taken from a standard textbook:

Again, the answer is perfect:

How should one score, and weight, homework?

Even before AI, I had been lowering the weight given to homework, from about 18% of the overall grade about 10 years ago to about 13% in recent instances. Now that AI can do every assignment perfectly and quickly it is hard to justify any weight as anything other than a penalty for the self-disciplined students. (Again, this applies to general-education courses — the environment in specialized or higher-level classes is different.)

It is tempting to lower the weight to zero, assigning homework but emphasizing that it exists as a tool to help students learn, and that it’s up to the student to use this tool and treat it seriously. The difficulty with this approach is psychological: there will be a sizeable fraction of students who, without the spur of a score, will not do the exercises and, as a result, will not learn as much as they would otherwise. Maximizing the understanding of energy-related topics among non-science majors is my goal for the course, and so this outcome isn’t ideal!

Alternatively, one could keep awarding points for homework, but these points could be based solely on completion rather than correctness. The difficulty here is that it is trivial to “complete” an assignment, again bypassing learning.

I think the best approach is to increase the number and weight of in-class assessments — quizzes and exams — and to decrease the homework weight a bit more, but not to zero, retaining the psychological spur of a score. I’ve noticed with things like post-class notes and participation points that the magnitude of a grade weight doesn’t matter much; anything non-zero is perceived as “real,” no matter how small. Coincident with this I should work on conveying to students, who are far more aware of AI than most faculty, the reasons behind this policy, the goals of homework and exams, and the wonderful opportunity they have to learn by any means at their disposal while being responsible for demonstrating what they can do.

Today’s illustration…

I painted a tomato.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy, September 17, 2025

I used to have the grade be 40% homework, 20% class participation, 40% final exam. Now I do it 20% homework, 40% class participation, 40% final exam. And I keep them busy during class!