Last term (Fall 2024) I again taught the computational image analysis course I developed a few years ago (see 2021, 2022). It was again a mixed graduate and undergraduate course, this time with an enrollment of 18: 14 graduate and 4 undergraduate. For a primarily graduate elective course, this is a large number of students; most of our non-required graduate courses don’t hit double digits. I was delighted by the diversity of the class: Ph.D. students from physics, chemistry, biology, and bioengineering; one Optics MS student; three Physics undergrads; and one undergrad from our data science major. The course went well. I didn’t change much from previous years, which may be a bit shocking given how rapidly the field is moving. Here’s a recap and self-assessment, especially reflecting on the motivations for the class.

The course is primarily about image analysis methods — concepts and algorithms — but incorporates physics, some statistics, and a bit of biology via the examples I use. The physics mainly involves optics: how images are formed and what determines limits on qualities such as resolution. The largest module of the course, and my favorite, goes from the appearance of point like objects, like stars or single molecules, to super resolution microscopy, in which an understanding of diffraction and statistics lets us transcend what we thought were unbreakable resolution limits. (It also leads to Nobel Prizes.) Students simulate images and write and test various particle equalization algorithms. The bulk of student work in the course is programming, with weekly assignments.

How (or why) should one construct an image analysis course?

The goal of scientific image analysis is to extract quantitative information from images. The tools and techniques of image analysis are changing at a dizzying rate. It’s hard to keep up! (My research relies heavily on image analysis, so being competent at it is relevant to more than this class.) This in itself would make it hard to design an image analysis course. However, there’s a much bigger issue to face: Image analysis is useful, but is learning its methods useful? These methods have traditionally involved devising algorithms to identify objects or features, such as edges, in images. I’ll refer to this as “classical” image analysis.

In recent years, however, the performance of artificial intelligence — i.e. machine learning models — has dazzled us all, and for many applications, including many scientific and medical applications, training a neural network to identify clusters of molecules or bacteria in a biofilm gives better results than bespoke, hand-coded algorithms. Is there, then, a point to learning classical methods and of making them the subject of most of the course?

I struggled with this question, eventually deciding “yes.” In retrospect, I reached the right conclusion, though I can easily imagine reaching the opposite conclusion in the near future. There were several reasons for my yes.

First, we’re not yet at the point where we can just give a computer all of our noisy, messy microscope images and ask it to identify, for example, all the different types of cells and report back with their positions and shapes. In contrast, I can ask Google Photos to identify my children in my digital albums, or to find all the images with a black bicycle in them, with stunningly accurate results. Off-the-shelf neural networks do now work well for simple scientific images, for example many 2D images of cells dispersed on a slide, but complex datasets especially spanning three dimensions are still not plug-and-play. This isn’t because they’re intrinsically more difficult than photos of human faces or bicycles, but because voracious neural networks haven’t been fed with millions of labeled training images.

Second, even if we could use machine learning, we might not want to. The decision making process of neural networks is notoriously, and inherently, hard to interpret. We might prefer to say “the objects with aspect ratio greater than X and volume less than Y are cells,” rather than “some property of these two million weight parameters distinguishes cell from non-cell.” The former may also help ensure the reproducibility of our findings.

Third, the combination of classical methods and artificial intelligence is a powerful one. We might process images in ways that can make pre-trained neural networks better able to handle them, highlighting particular features for example. I was delighted to hear this echoed by a former Ph.D. student of mine, Philip Jahl, who is currently employed doing computational image analysis at Canfield Scientific, a biomedical imaging company. We chatted a few months before the start of the term; Philip assured me that learning classical methods, even though much of what he does involves AI, is useful!

Finally, classical image analysis is an elegant and interesting subject. I’ve enjoyed learning it, practicing it, and even contributing to it, and I hope others will as well.

Course Topics

The course, then, kept a similar structure as in the past. The description and syllabus are here; the topics are listed on page 3. Our terms are ten weeks long, plus an exam week. This flies by quickly!

As in the past, rather than a final exam I assigned a final project in which students explored a topic that builds on subjects seen in class. My list of suggested topics is below, with italics indicating one chosen by students this term. One pair of students chose a topic not on this list, ptychography, which I enjoyed learning about.

Topics

- De-noising

- Localization-based Super-Resolution Microscopy: 3D!

- Localization-based Super-Resolution Microscopy: Further Topics

- Image Analysis in Cryo-Electron Microscopy

- Deconvolution (beyond what was covered in class)

- Image Reconstruction in Tomography

- Segmentation – beyond Watersheds

- Light Field Imaging

- Multi-spectral / Hyper-spectral Imaging and Image Analysis

- Structured Illumination Microscopy

- Holographic Microscopy

If there were more time, I’d insert a few of these topics into the regular course content. One would be tomography, whose various manifestations in medical imaging such as CT scans are immensely powerful and whose theoretical underpinnings are clever and elegant. Another would be structured illumination microscopy, in which making patterns of light and dark enhances the resolution of the resulting images through a method reminiscent of radio broadcasting. (I might make a blog post about this.)

A bit of machine learning

I felt it important to give some exposure to machine learning in the course, but given the constraints of a ten week quarter we could only spend a few classes on it. My goals were (1) to give a sense of how non-neural-network methods like support vector machines work (elegant, but not state-of-the-art), and (2) to introduce the basic idea and current state of neural networks, especially as applied to images and computer vision. For the first goal, I didn’t go through the theory or ask students to write their own algorithms, unlike all the preceding parts of the course, as enjoyable as both these activities are. We could, however, assess support vector machines using the same sort of single-particle images we used earlier in the term, seeing if the machine could learn to discriminate, for example, between images with one or two light emitters.

For the second goal I started with the perceptron, a fully connected neural network to use the modern terminology, first built in the late 1950’s! Even half a century ago, this machine could “see” signs with letters on them and learn to identify the letters. We then skipped a few decades in which not much happened to get to modern neural networks and methods for training them. We discussed convolutional neural networks, which nicely mirror the “classical” uses of convolutions that students worked with earlier in the course. Again, students didn’t write their own training code or backpropagation algorithms, both of which are great exercises. (See this course, which I noted in my 2022 post.) That brought us to the current dominant method, the shockingly powerful transformer network architecture that underlies models like ChatGPT and Claude. Sadly, I haven’t had the time to try to implement these “from scratch” myself [1, 2]. However, I was delighted to find, a few months before the term started, this new book on computer vision: Foundations of Computer Vision by Antonio Torralba, Phillip Isola and William T. Freeman (MIT Press; 2024). Not only is it excellent in general, it has a clear, well-illustrated description of attention layers and transformer networks. I borrowed heavily from it for this part of the class.

Course evaluations, and a question of scaling

I enjoyed teaching this course quite a lot. The topic is fascinating and the students were enthusiastic and great to interact with. The students seemed to like the course as well. The end-of-term student survey was uplifting to read, with “Truly excellent course!” and “By far the most useful class I’ve taken at UO” being some of the comments.

I specifically asked the students to comment on whether this class could scale to be significantly larger. (I don’t know if there will actually be the opportunity to attempt this, but that’s a separate issue. One would think there would be demand from undergraduate data science majors, but so far that isn’t the case.) The students emphasized the homework as the biggest challenge for scaling up. The homework assignments were difficult, and students noted that having one-on-one or small group interactions was crucial to being able to complete, and learn from, the homework. This would be hard to replicate in a large class.

There may be ways around this: 1. Rather than students writing so much from scratch, I could pre-supply more code and students could fill in pieces. This removes, however, one of the key skills developed in the course, the ability to write code without much scaffolding. (I think too many students get used to simply filling in a cell of a Jupyter notebook and then are lost when faced with new tasks.) 2. Students could use AI tools more to debug their code. I was a bit surprised at how little this was being done currently. Making this a useful way of learning would be helped if I structured the assignments on these lines, for example with questions that spurred students to design test cases. Somewhat related: It was clear that students weren’t using AI to write the important parts of the code for them, which I’m sure is a consequence of the class being a small, self-selected group of students who want to develop their skills, in contrast to a large or lower-level course. 3. I could make the coding assignments count for a smaller part of the grade, and introduce exams. This would change the nature of the course considerably. It might be necessary for other reasons — I don’t actually test students, for example, on their understanding of optics or Fourier transforms, relying on the small size of the class to get a sense of their understanding beyond what’s reflected in the homework. Perhaps a larger course would necessarily be a very different one.

Regardless of size or form, I don’t know when this class will be offered again! The students were emphatic about its value, but it doesn’t fit well into the usual categories for course offerings. (Officially, it’s still an “experimental” course.) We’ll see!

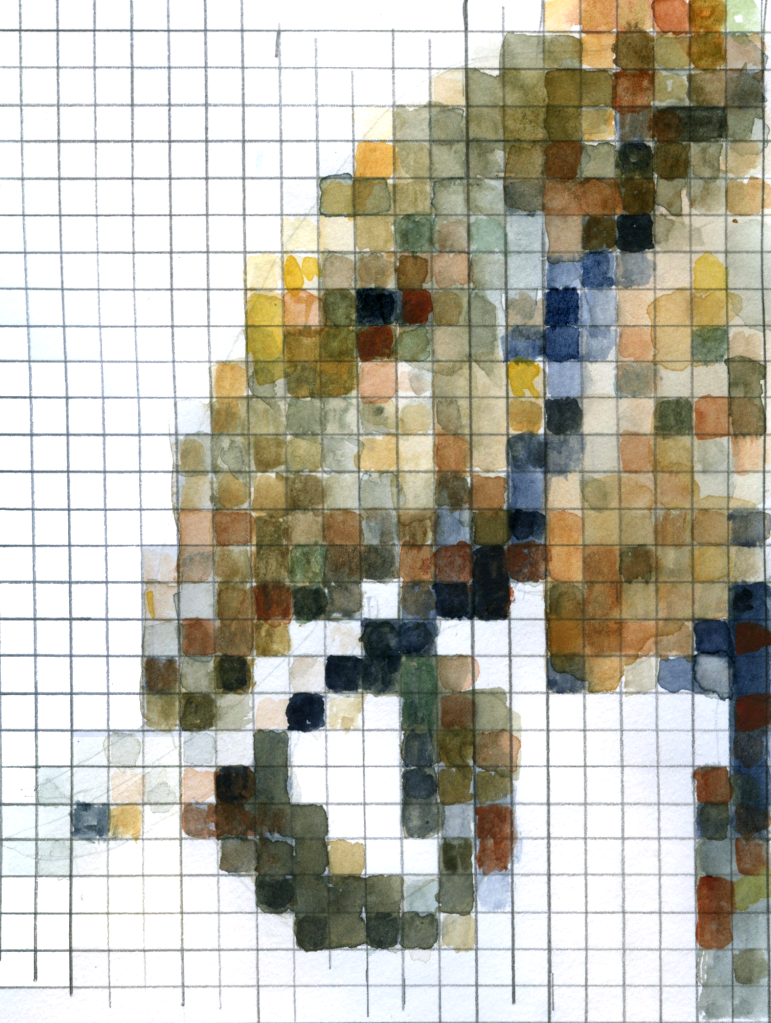

Today’s illustration…

I painted some pixels.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy, January 9, 2025

Notes

[1] Exercises on this would be in the U. Michigan course noted above, whose second half has remained on my “to do” list for years. Complicating things, transformers are covered in the 2022 version of the course, but not the 2019 version whose video lectures are available. The homework is quite hard even with videos!

[2] See also, “Let’s build GPT: from scratch, in code, spelled out.” YouTube, by Andrej Karpathy, which looks amazing, but which I haven’t worked through. (Over 5M views!)