Once again, highlights of the books I read in the past year, featuring the end (for now) of my education in twentieth-century semi-organized crime, a book on semi-organized twentieth-century chimpanzees, and more. (Previous years: 2023, 2022, …, 2015.)

Books by people who passed away in 2024

The best non-fiction book I read this year was James C. Scott’s Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998). (Technically, I listened to this as an audiobook; I’ll use “read” for both reading and listening.) Seeing Like a State is well known for good reason; it’s a fascinating exposition of how states, bureaucracies, and planners impose order on the variety of human activities, often with disastrous and dispiriting consequences. The book is relentless in its description of how the modernist desire for rational, quantifiable schemes run roughshod over local knowledge, autonomy, and even happiness. Late 19th century foresters, for example, plant grids of single tree species, leading to ecological failures decades later. The pattern repeats, as both colonial and governments and newly independent African nations impose, often with force, grid-like villages and collective farms regardless of terrain or local insight. Scott has a special hatred of Le Corbusier, who he paints, largely through quotes from Le Corbusier’s own writings, as a misanthrope bent on forcing humans into the mold defined by his planned cities and boxy buildings. Much like Martin Gurri’s excellent “The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium” (which I noted in 2021), Seeing Like a State colors everything you see after reading it, explaining many aspects of how the modern world works.

Scott passed away in 2024, news of which spurred me to read Seeing Like a State. Another 2024 death was Frans de Waal’s, and so I read Chimpanzee Politics (1982), a classic book of observations of a chimpanzee colony at a Dutch zoo, focusing especially on “politics” – strategic maneuvering and planning to achieve positions of dominance. It’s a wonderful and very readable book. The similarities between chimpanzee and human behavior are striking, and they highlight the biological basis of complex behavior. I found the struggles of the chimpanzees a bit sad – they spend so much time scheming and fighting (or threatening to fight) despite having all their needs, like food, taken care of. The struggle is unnecessary but is hard-wired, which holds lessons for our current human age of abundance.

I thought perhaps, like reading several books from 1965 last year, reading books by people who passed away in 2024 could be a unifying theme, but I didn’t find other books that I was keen on reading that fit this category. Maybe Cormac McCarthy, who died in 2023, is close enough; All the Pretty Horses (1992) is a stunning novel about two teenage boys in the mid-twentieth-century who leave Texas for Mexico, on horseback, finding work as well as a series of misfortunes. It’s an amazing combination of realistic, vivid characters, lively dialog, and poetic description of the beautiful, but cruel, universe. I also read The Crossing, the second book in the Border Trilogy begun by All the Pretty Horses, which I thought wasn’t nearly as good.

Speaking of movies…

… All the Pretty Horses was made into a film, which I haven’t seen. True Grit and Strangers on a Train are films I have seen, both based on books that, before this year, I hadn’t read. True Grit is wonderful, a charming, fast-paced, often funny story of a teenage girl in the Old West who sets out to avenge her father’s murder. Strangers on a Train gets off to a good start — strangers meet on a train, murder plans ensue — but the second half drags on, losing momentum and straining credulity. I should re-watch the Hitchcock film, which I’m sure is more taut.

Speaking of stories in multiple formats…

This year I read Butcher’s Moon, in which a criminal wants to recover the money he stashed earlier at an amusement park, which leads to a fight with the local organized crime outfit, amid infighting within the mob. This doesn’t sound particularly remarkable, except that it’s Book #16 in Richard Stark’s “Parker” series of crime novels, the original 1962-1974 run of which I have now completed. (The series resumed with new books in in 1997; perhaps I’ll read those.) The Parker novels, which I wrote about last year and the year before, are captivating. The stories of heists and double-crosses don’t aim to be great literature, but they’re entertaining. Reading the whole set conveys a sense of what it took to plan and communicate before computers and cell phones, and, as one absorbs thousands of pages of schemes, worries, and disappointments, one can’t help think about how we all give shape to our lives and careers. In addition to finishing book #16, I re-read books #1 and #2 (The Hunter and The Outfit), not as novels, but as graphic novels, adapted and illustrated by Darwyn Cooke. Both were enjoyable, with excellent bold and minimal illustrations. I wondered how comprehensible they would be if I hadn’t read the books, though, and I also asked “Why read this?” It’s not like the originals are hard to access or understand. I’m also skeptical that we gain any insights from the pictures. There’s nothing wrong with them, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was no real reason for these books to exist.

A book that should exist, and does

In contrast, a biography of Frank Ramsey definitely should exist, and it does: Frank Ramsey : a sheer excess of powers by Cheryl Misak (2020). It’s an exhaustive book, perhaps appropriately so given that its subject was a remarkable philosopher / mathematician / economist of the first part of the twentieth century who would likely be as well-known as Turing, Gödel, or Wittgenstein had he not died at the age of 26. The book is hard to evaluate. On the one hand, Ramsey is fascinating – astonishingly brilliant, broad in his interests, a warm and friendly person according to everyone who his brief life intersected, and a participant in one of the most intellectually vibrant environments ever during which the foundations of math and philosophy, as well as social mores, were being questioned and rebuilt. On the other hand, the book is painstakingly thorough and would benefit from being half its length. I listened to the audiobook, which was 19 hours and 55 minutes long! Almost all my audiobook listening is done while running, but for this I sometimes listened to parts with my phone in my shirt pocket while biking home and I didn’t mind if traffic drowned out some of the words. An audiobook isn’t the ideal format for this book; there are sections describing logical or mathematical equations and hearing someone recite “for all x subscript j in the set A superscript q, x subscript j implies y…” (or things like that) is comically ineffective. The introductory chapter gives an excellent overview of Ramsey’s life; perhaps one should just read this. In any case, reaching the last chapter, on Ramsey’s death from jaundice likely derived from a bacterial infection, was genuinely sad; I had come to appreciate and admire this phenomenal person who died so young.

In contrast, good, short non-fiction

Two excellent non-fiction books I read were very short, and their brevity helped them: The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of the African Middle Ages by François-Xavier Fauvelle (2013) is a series of short pieces about Africa between roughly 900 and 1500. Not knowing much about African history, I thought it was great – brief glimpses of a wide range of topics, mostly centered on trade since much of our knowledge comes from the writings of traders. A recurring theme is how little we know, with whole towns being lost (in the Sahara for example), archeology being fragmentary and difficult, and writings rare. Still, what we know paints a fascinating picture. It’s true that many of the chapters left me wanting more, but that’s what other books are for.

Bitter Lemons of Cyprus by Lawrence Durrell (1953) is a memoir of a few years spent in Cyprus in the early 1950s, when Cyprus was agitating to be free of British rule and to join Greece. The author is the brother of Gerald Durrell, author of the entertaining My Family and Other Animals. The first half of this short book relates pleasant observations of settling in to Cyprus – making friends with Cypriots, bargaining over a house purchase, etc. In the second half Durrell is an observer of, and in a small way is involved in, the political turmoil. The juxtaposition of the two halves is bizarre, but this is what makes the book especially interesting; a superficially idyllic world still has conflict and violence. Durrell is a strange narrator and his omissions make the book fascinating. In passing, near the end, he mentions a daughter; the reader has no idea of her existence otherwise, and Wikipedia informs me that the 2-6 year old girl was with Durrell on Cyprus! Durrell’s economic situation is also unclear; he is rich enough to buy a house at the start, though not an expensive one, but he takes various jobs in the second half including a public relations position with the British government. The decline of the British Empire even beyond Cyprus is in the background of this book. As always, I’m amazed by how few British people it took to rule half the world. Here, we see a local view of how haphazardly and chaotically the empire ended, though the book ends before Cypriot independence.

Both these books get poorer reviews than they deserve, maybe because people want them to be more complete than they are.

Favorite fiction

My favorite of the fiction I read this past year (with an exception that shouldn’t count, noted in the next paragraph) was The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1967), a wild fantasy about the devil and his sidekicks causing chaos in contemporary Moscow, historical / mythological fiction about Jesus and Pontius Pilate, and satire about Soviet Russia, all in one novel. It’s unlike anything else.

Also notable: two books picked up from the university library’s “popular reading display,” just because they looked interesting. Kalmann by Joachim B. Schmidt (2020) is about a mentally disabled Icelander is caught up in a mystery in his rural, disappearing town. It’s charming and enjoyable, with glimpses of broader issues of societal change like urbanization and immigration. The main flaw is that the though the narrator is mentally challenged, the narration can’t consistently represent this – he often seems sharper than is plausible, since the story requires it. (It’s no “Flowers for Algernon” in terms of narrative skill). In Warlight by Michael Ondaatje (2018), two teens are left in the care of vaguely criminal guardians just after World War II, and their mother’s connections to espionage are slowly revealed. The first half is wonderful; the ending is flat. And one more book to note, since I’ll probably finish it this evening: James by Percival Everett (2024) — very unusually, a book I read that was published within the past year! It retells and expands upon the story of Jim, from Huckleberry Finn. It’s a quick, entertaining read. If it weren’t for the book jacket and a few reviews I looked up, I wouldn’t have guessed that it has pretentions of literary greatness and was a Booker Prize finalist — it lacks depth, and Jim is such a flawless example of wish fulfillment I half expected him to fly.

I also reread Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, to see if I’d like it as much as I remembered. I was relieved to find out “yes,” and I think it’s actually even better than I remembered. If I had to name a favorite novel, this would probably be it. A page-turning mystery, a historical novel, a chronicle of the birth of scientific thinking, an allegory of how science attempts and doesn’t quite succeed at following a method.

This post, similarly, doesn’t quite succeed at sticking to themes, but it’s adequate….

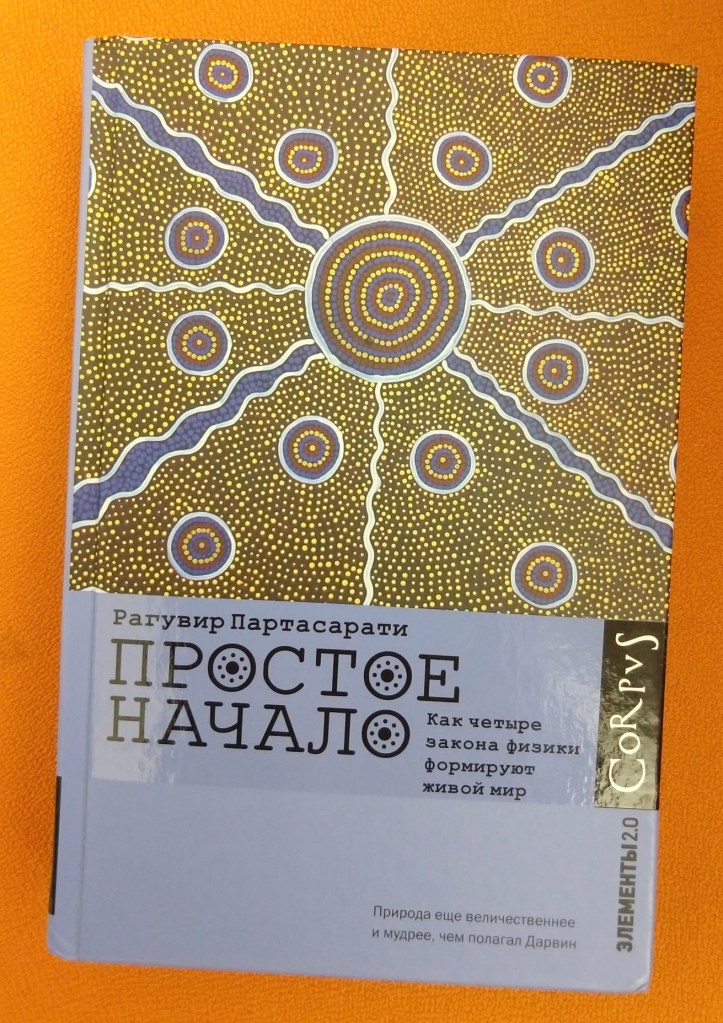

(Added after the original post, when I remembered!) Also in 2024, the Russian translation of my pop-science biophysics book appeared!

Today’s illustration…

I painted this from a photograph by William Eggleston in this book. Here’s a photo of the photo.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy, December 30, 2024