Perhaps when blowing your nose, or the nose of a sick child, you’ve wondered where all this stuff comes from. How can one nose make so much mucus? This is #17 in our series of biophysical questions (#1, #16). The answer involves electrical forces and the physical character of mucus.

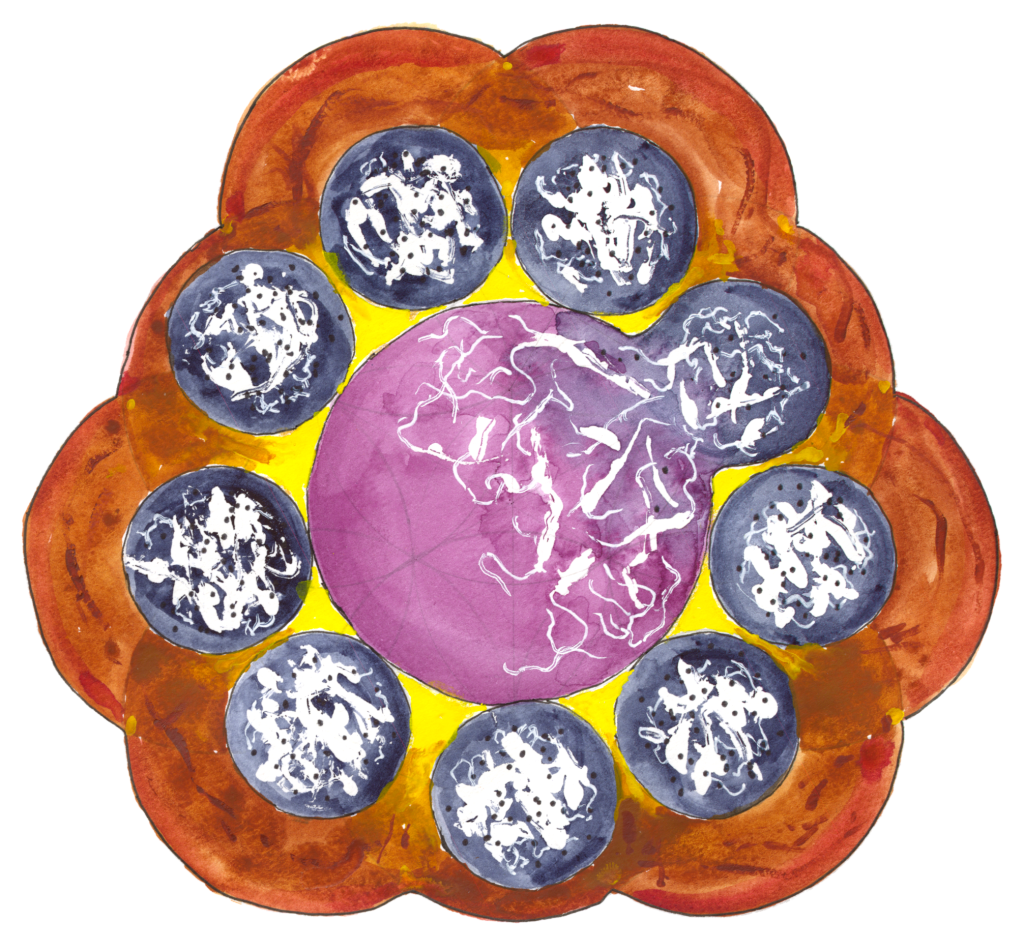

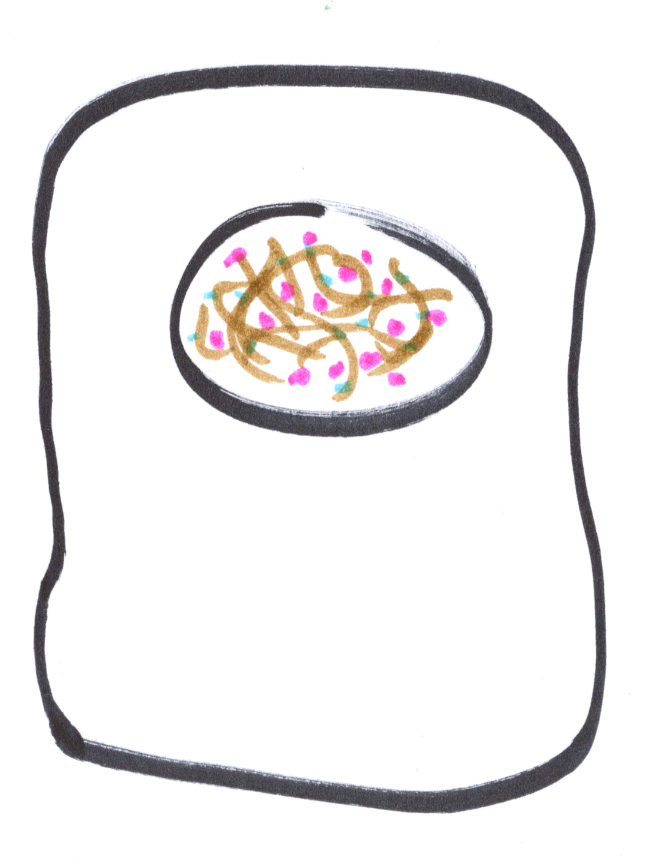

Mucus, the gooey liquid secreted by your nose as well as by the linings of other body parts, is made of polymers — long, string-like molecules. The polymer molecules are negatively charged; imagine lots of speckles each with one electron’s worth of negative charge along each string:

For every negative charge, there’s a positive charge somewhere, an ion floating around in the watery medium. If these are “+1” charges, like sodium ions (Na+), the polymer network will be fairly expanded due to repulsion between the negative chains. (The cause of the repulsion is subtle — it’s not Coulomb’s law that you may have learned about in a Physics class, but rather a consequence of entropy [1].) If, however, there are “+2” or stronger charges, like calcium ions (Ca2+), these heftier ions lead to collapse of the network, in part because a +2 ion can bridge two -1’s on adjacent polymers [2].

In secretory cells, mucus is stored in membrane-bound compartments that are rich in calcium ions; the mucus network is compact.

When the mucus is released into your nasal passages, it finds itself in a low-calcium environment, and the calcium that accompanied it quickly diffuses away. The mucus therefore expands. It can expand a lot, increasing its volume a thousand-fold [3].

This prodigious production was celebrated by Shel Silverstein:

I shared this poem with my Biophysics class a few weeks ago, to launch our look at electrostatics.

Today’s illustration

Doodling with circles vaguely reminiscent of mucus secretion.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy November 30, 2023

References

[1] To learn more about electrostatics in water — a fascinating topic — I recommend (i) Philip Nelson, Biological Physics Student Edition: Energy, Information, Life (Chiliagon Science, Student ed. edition., 2020). (ii) J. Israelachvili, Intermolecular and Surface Forces (2nd edition) (Academic Press, New York, 1991).

[2] Here, too, there’s much more to the story. See for example O. Matsarskaia, F. Roosen-Runge, F. Schreiber, Multivalent ions and biomolecules: Attempting a comprehensive perspective. ChemPhysChem. 21, 1742-1767 (2020).

[3] The greater pH in the extracellular environment also helps; see for example the references in Pelaseyed et al. Immunol Rev.260: 8-20 (2014); Birchenough, G., Johansson, M., Gustafsson, J. et al. New developments in goblet cell mucus secretion and function. Mucosal Immunol 8, 712-719 (2015).

I love Shel Silverstein!

The connections among art, science, and learning are beautiful. Your simple diagrams reduce the cognitive load by connecting thinking and doing with understanding, as Temple Grandan always emphasizes.

Thank you!

Thanks Raghuveer. My friend asked ‘why there is more mucus when one has a cold or when we are outside in cold weather’. I thought it is to do with the humidity in the air and the moisture in the exhaled breath. Is there a better explanation?

That’s a great question! I’ve been told that cold air (which is drier than warm air) stimulates more mucus secretion in order to maintain the moisture of nasal passages. A similar thing happens for the eyes — when bicycling, my eyes water a lot if it is cold out — the tear ducts are trying to keep my eyes moist, and mine tend to overcompensate.

Thanks Raghuveer, for your swift response. The physical chemistry of air and water plays a vital in so many processes in nature.