Biophysics is full of deep puzzles that are surprisingly simple to state. Imagine a pill shaped bacterium. (Your body is home to trillions.) It grows and then cleaves itself into two equally sized progeny. How does it know where its middle is?

For us, looking at the bacterium, finding the middle is an easy task. We can imagine holding a ruler to the cell or (more realistically) counting pixels in a microscope image, finding the point halfway between the ends. The bacterium, though, lacks a perspective external to itself, not to mention eyes or rulers. You might like to ponder possible strategies; perhaps imagine yourself inside a capsule full of jittering proteins, tasked with finding the middle. Even if you had eyes, the wavelength of light isn’t much smaller than the capsule, so seeing where the center is isn’t an option. You can measure time but only very crudely — certainly not well enough to time anything bouncing off of one side or another, even if you could discern such a signal over the tumultuous background. You can, however, measure the concentrations of chemicals such as proteins. Some of these proteins can bind and unbind from the walls (the cell membrane). Some can perform chemical reactions such as altering other proteins’ affinities for the membrane. These abilities, it turns out, suffice to generate waves; using the waves, you can find your center. How?

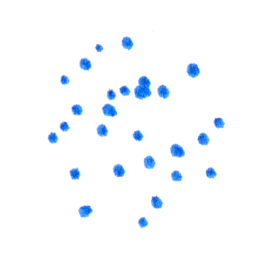

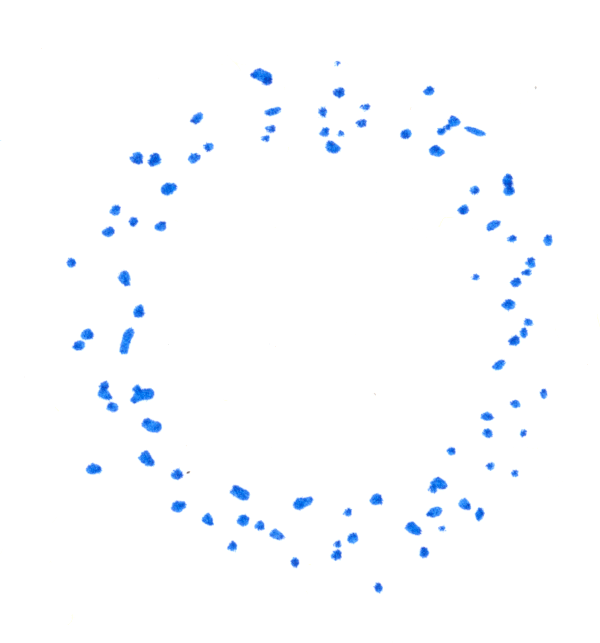

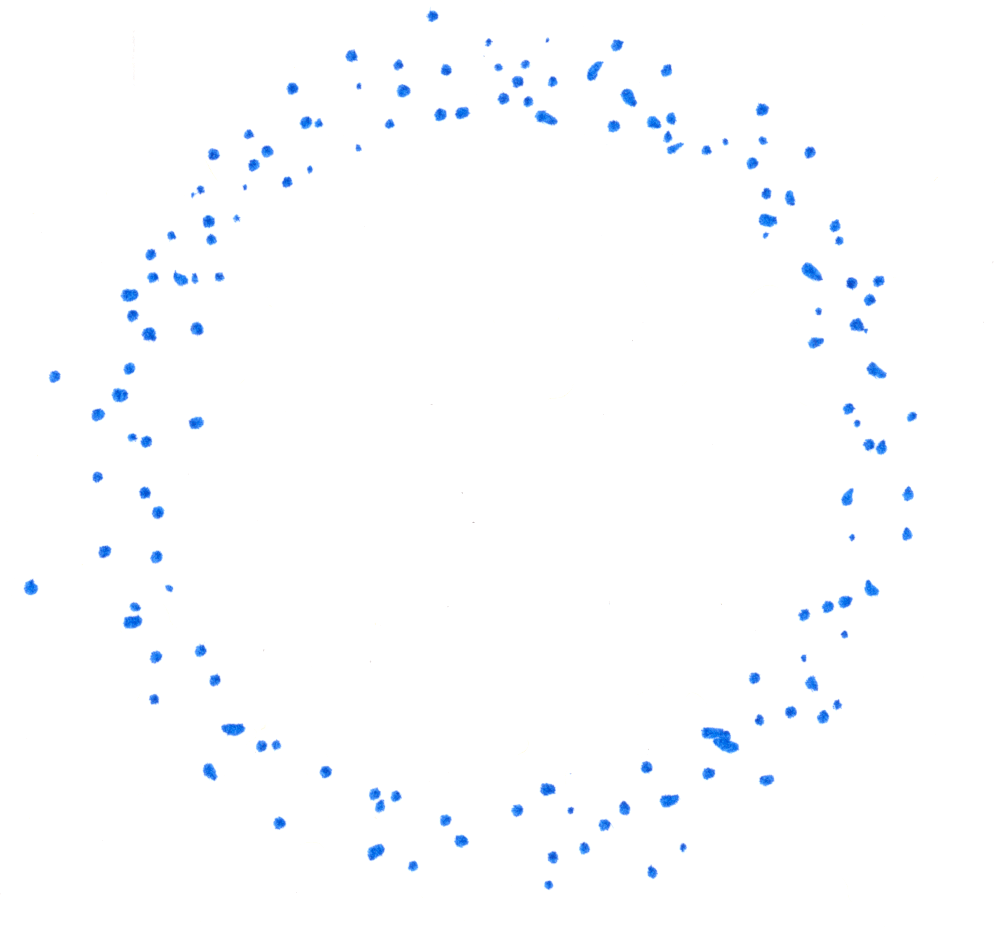

As always in this series, I emphasize the question and only briefly describe the answer. The key players are two proteins called MinD and MinE. MinD has two configurations, one of which has a much higher affinity than the other for binding to the bacterial membrane — this form is dark blue in the sketch below. Moreover, MinD is more likely to bind at the edge of a pre-existing MinD patch. MinE, pink in the drawing, will bind to membrane-bound MinD and induce MinD to switch to the low-membrane-affinity form (light blue). Imagine a patch of MinD at a membrane:

MinE proteins bind amid the patch, as do new MinD proteins at the edge of the patch.

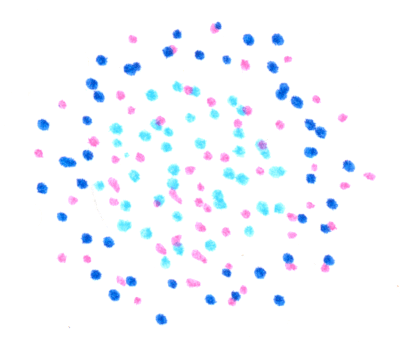

The central MinD are transformed into the low affinity version. New MinE associate with the outer ring of MinD.

The central MinD unbind and diffuse away, and those of the first ring are transformed by MinE into the low-membrane-affinity form..

The process repeats, giving a new further-out ring,

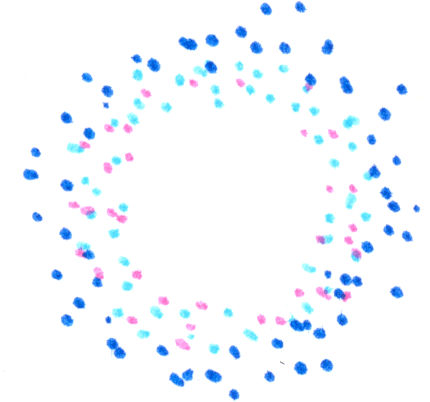

a still further-out ring,

and so on, all traveling outward. (There can be an inward-directed ring also, which I haven’t drawn.) Of course, we started this illustration with a circular patch, but however we start we’ll have a band of membrane-bound MinD that travels along the membrane with some speed set by the time scales for these bindings and conversions. ln the bacterium these waves of MinD concentration slosh about along the inside walls, back and forth along the rod-like body, turning around at the ends. The location with, on average, the least MinD is the middle. The bacterium divides where a ring composed of a different protein assembles, pinching the cell body. This protein, via an intermediary, is inhibited by MinD. Its most likely location, therefore, is the middle of the cell!

This clever use of spatial oscillations is how the intensely studied bacterium E. coli sets its division plane. It’s likely a common mechanism among bacteria, though I know of one other fascinating strategy, and there are undoubtedly others waiting to be discovered. E. coli’s remarkable Min protein dynamics were only discovered about 20 years ago. If you’d like a longer, few page, explanation of the Min system, there’s an excellent one in the great Physical Biology of the Cell textbook by Rob Phillips, Hernan Garcia, Jané Kondev, and Julie Theriot. The book also cites primary papers, including beautiful work by Petra Schwille’s group reconstituting Min proteins on artificial, planar membranes and watching the Min waves drift along (movie).

Min oscillations and the challenge of finding one’s center are absent from my pop-science biophysics book, though there’s plenty of bacterial biophysics and other puzzles of spatial patterning, for example how your thumb ends up on the proper side of your hand. The usual book links : My description, the publisher, Amazon.

There are still many open questions regarding cell size; even less is known when many cells are involved. How for example do your arms end up the same length? That remains a mystery!

Today’s illustration

The Vitruvian bacterium.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. July 1, 2023