How many books are published each year? I’ll provide some numbers that were a surprise to me when I learned them a few years ago. First, some context. At the American Physical Society “March Meeting” two months ago, I was part of a workshop on Communicating Biological Physics. Four of us gave presentations and led discussions on various aspects of this topic. Here’s a link to the poster I made, which lists the presenters and presentation titles.

I focused on communication with non-scientists, part of which involved describing the motivations and the process of writing a book. If you’re read any of my posts from the past year, you’ll know that I write a pop-science book on biophysics, described here. I led off with reasons not to write a book:

- It’s a lot of work.

- Hardly anyone will read it (unless you’re already famous).

#1 is well known, but it can’t be underestimated. Writing a 250 page book is much more than 25 times harder than writing 25 10-page essays. About #2 I’m exaggerating, of course, and I will emphasize that I’m quite happy with my book’s sales (as is my publisher), but the point is worth elaborating.

There are a lot of books out there. According to a 2010 analysis by Google, “a lot” is about 130 Million, though the uncertainty is large. I like to wander through the university library aisles, amid shelf after shelf of books, all of which took their authors considerable effort and which would take many lifetimes to consume. The accumulated books of the past provide competition for any new book.

So to do the books of the present, of which there are a staggering number. Guess, I asked my workshop attendees, how many new book titles are published each year? (You can pause and guess…, and in the meantime here’s my then-nine-year-old at the Art and Architecture Library, doing his part to ensure that old books get read.)

How many books are published each year?

The order-of-magnitude answer: about a million. Each year! (That’s not a million copies, but a million titles, many copies of each of which, its author hopes, will be produced.)

An exact answer is elusive. As many sources note [1], there isn’t a publicly-available database of publishing statistics. NPD BookScan provides detailed data covering the majority of book sales in the U.S., but a subscription is about $2500 per year [2]. This is cheap compared to the extortionate cost of academic journals, but is outside the budget of a casually interested person like me. We’re left scouring the internet for estimates, which unfortunately span a fairly large range:

- “…over 2 million new titles were released worldwide last year [2010]”, with about 300,000 in the U.S. — from “Worldometers” (http://www.worldometers.info/books/), listing a UNESCO study as its source.

- There were 3 million new book titles in 2011, and 300,000 in 2003, according to “numbers reported by R. R. Bowker LLC” reported in https://malwarwickonbooks.com/published-every-year/

- “About 4 million new books were published in 2022” — from https://wordsrated.com/number-of-books-published-per-year-2021/; of these about 2 million are self-published, according to the same site and https://www.tonerbuzz.com/blog/how-many-books-are-published-each-year/

- Penguin Random House, the largest publishing house in the US, publishes 85,000 titles/year (15,000 print, 70,000 digital) — https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/imprints (2022?)

- Adult non-fiction is the largest category of books sold, making up about 40% https://wordsrated.com/book-sales-statistics/.

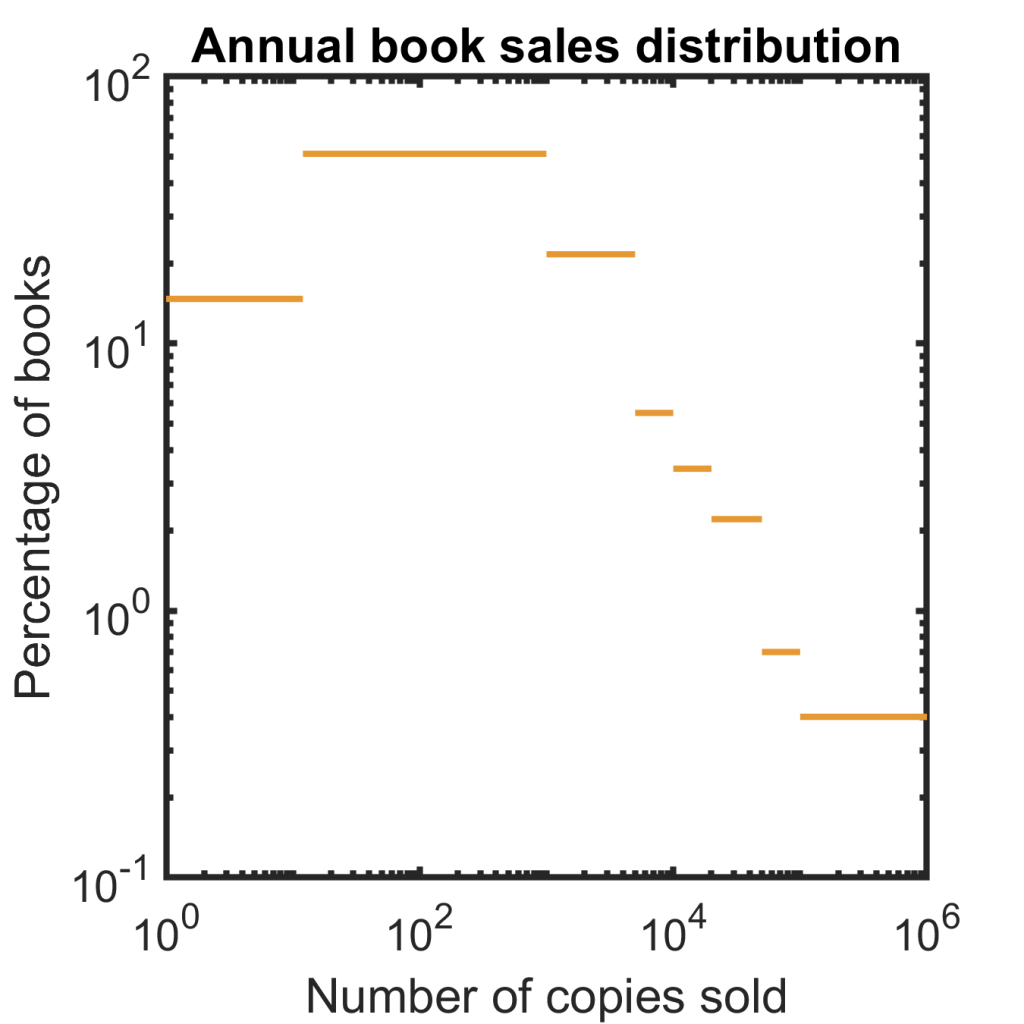

The flood of books means, of course, that most books don’t sell many copies. For more on this, see this excellent essay, “No, Most Books Don’t Sell Only a Dozen Copies” — and especially the insightful comment from Kristen McLean, an analyst with NPD Bookscan. She notes that publishers gamble on a small fraction of books selling many copies; money is made from the tail of the distribution. She even provides numbers for the United States, for all books rather than new titles, I think, which I’ve plotted here:

About 2% of titles, for example, sold between 20,000 and 49,999 copies in one year, and about 20% between 1,000-4,999 copies.

Returning to book-writing: your book will be one among hundreds of thousands, if not millions, released every year.

AI and books

It seems almost mandatory that every essay or blog post in 2023 comments on artificial intelligence or the amazing Large Language Model neural networks that have recently emerged. (See my past post, for example, on their exam performance.) We’re already seeing people use LLM chatbots as a writing tool, for junk like spam and marketing fluff, but also for essays and even novels — a person quoted in this article suspects he could churn out 300 per year. One may find this dismaying or worrying (as I do), but regardless, one can ask what it will do to the number of books published.

I would predict that it further increases the flood of titles, as the AI assistants contribute text in response to human prompts. The barrier of a blank page will become less daunting. (I fear that the uniqueness and variety of how humans fill that blank page will decline.) Our recent history may tell us how we might deal with this expected super-abundance of books. We’ve already seen a tool that makes book generation much easier: internet-enabled self-publishing. Self-publishing has always existed, but e-books, printing on demand, and Amazon have made it simpler, cheaper, and more widespread. As noted above, there are millions of self-published books released each year — over half the new titles (probably). What do we do with these? Mostly, we ignore them.

We are certainly discarding some gems, but we generally take books that go through the traditional publishing process more seriously than self-published books. Editors, and maybe also agents and others, have vetted and hopefully improved the manuscripts, and more importantly have been convinced that this may be something people will want to read. For self-published books, this may or may not be the case; we (or libraries or bookstores) act accordingly. Similarly, we might expect that an abundance of AI-facilitated books forms a background hum that’s largely ignored.

However, it seems hard to imagine that AI-augmented books won’t deluge traditional publishers and editors. It’s already hard to get their attention; this will get worse. I predict that various markers of status — university affiliations, awards, irrelevant notoriety — will be used for gatekeeping, even more than is currently the case.

Reasons to write

In the workshop, I briefly commented on reasons to write a book, most importantly that :

- You think there are gaps amid the books currently in existence — amazing stories that are unknown and fascinating topics that are under-represented. (This certainly applies to Biological Physics.)

- You feel compelled to write.

Item 2, irrational compulsion, was especially appropriate to the conference location: Las Vegas.My friend and co-presenter Phil Nelson provided a quote that says this more dramatically:

There is no use whatever trying to write a book unless you know that you must write that book or go mad, or perhaps die. — Robertson Davies

Today’s illustration

A cactus.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. May 10, 2023

[1] For example, Harvard Library’s “Ask a Librarian,” Link

[2] https://www.publishersmarketplace.com/bookscan/about.cgi ; about $3k/ year if one wants data on electronic as well as print books.

When I was a young professor I wrote a book. The motivation was the usual thing: I was teaching a class for which there was no good textbook so I was using my notes. I turned the notes into a book, adding a lot in the meantime. One day my department chair, a genial middle-aged man who was well respected in the field of statistics, came by and said he heard that I was writing a book. He gave me the advice that this would not be good for my promotion to tenure. I replied that I’d rather publish the book than get tenure. And, a few years later, I got my wish!

That’s wonderful / terrible. Perhaps this should be the dedication section of your next book — to your former dept. chair, for selflessly enabling greater and longer-lasting contributions to statistics than his own!