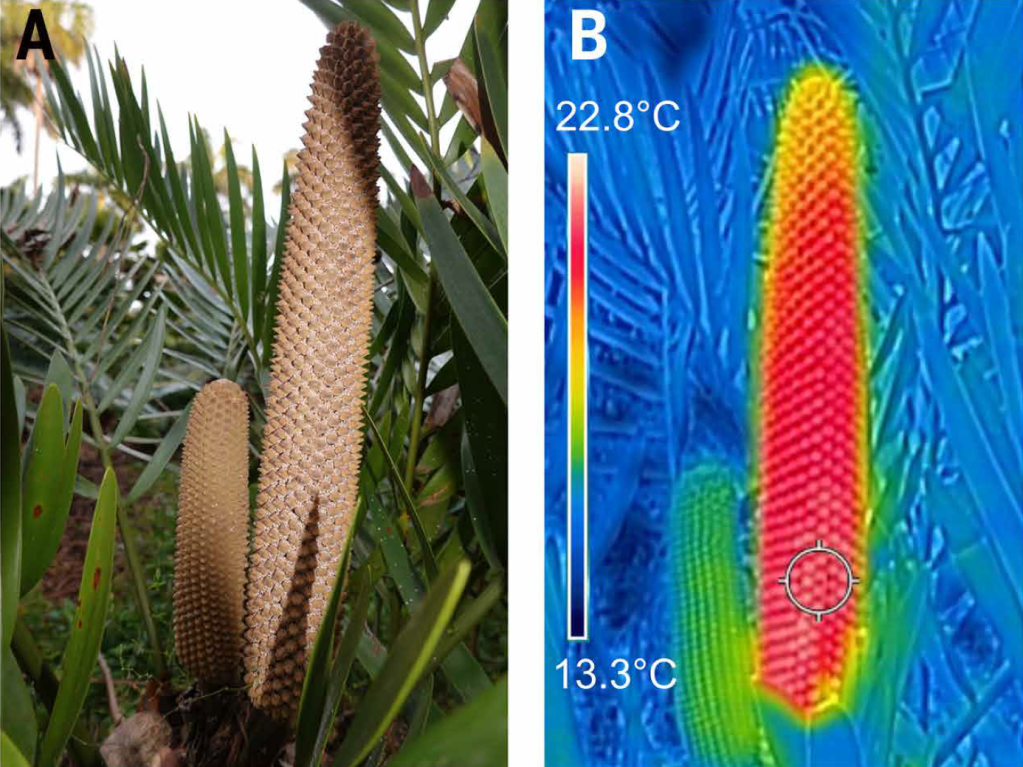

There are basic facts about the living world that we learn when very young. One is that mammals and birds are warm-blooded. More technically, mammals and birds fall into the category of endotherms, organisms that use internally-generated heat to maintain some preferred body temperature, and I always supposed that the omission of other creatures from this list implies that those other creatures are generally not endotherms. I was therefore shocked by a fascinating paper published in Science a few weeks ago, “Infrared radiation is an ancient pollination signal,” from which I learned that (1) some plants keep parts of themselves hot, up to a staggering 35 ºC (60 ºF) above the ambient temperature, (2) the infrared light from hot flowers or analogous organs is sensed as a cue by pollinators such as beetles, and (3) this thermal communication between plants and pollinators has existed for hundreds of millions of years, likely predating the perception of colorful flowers. Apparently, #1 has been known for a long time, just not by me. Item #2 was hypothesized but unproven, and #3 was, I think, unknown. The article: Valencia-Montoya et al. Science 390:1164-1170, 11 Dec. 2025, link.

Valencia-Montoya and colleagues not only confirm that certain plants generate heat that serves as a signal for pollinators and that pollinating beetles recognize this thermal signal, but they moreover identify the sensing organs, specific neurons, and even the proteins responsible for this thermal recognition and, by comparing the optical spectra of a variety of plants and the color-sensing proteins of a variety of pollinators, they determine that thermal sensing by pollinators likely arose about 275 million years ago, before the proliferation of color-sensing pollinators. Every section of this paper could, on its own, be an impressive article.

Before writing a bit more about the study itself, I’ll remind the reader of thermal radiation (i.e. blackbody radiation). Everything emits light, an unavoidable consequence of unavoidable microscopic motion. The jittering of electrically charged protons and electrons generates electromagnetic waves. The greater the temperature, the more radiated power and the shorter the average wavelength. (Equivalently, we can think of the object and a bath of photons in equilibrium at some temperature; this framework is easier to work with in practice.) An object like the sun, with a surface temperature of about 6000 K has the most emission at wavelengths around 500 nm, firmly in the range we see as visible light. Rocks, seashells, and you and me, with temperatures around 300 K (a few tens of degrees Celsius above freezing) have peak emissions around 10,000 nm, in the infrared range that our eyes don’t perceive, but that we can feel as heat. All this we learn as undergraduates, and I’m always excited when teaching these concepts to point to examples and consequences — the cosmic microwave background radiation that pervades the universe, for example, or the radiative equilibrium between the earth receiving visible light from the sun and radiating infrared light into space, which keeps the planet warm. Now I can point to another example: hot plants, and their perception by pollinators.

Valencia-Montoya and colleagues examine cycads, plants that look like (but are not) palms and whose cones are analogous to flowers in flowering plants. The heat production of the cones has a sharp circadian signature, turning on in a few-hour window around dusk. To establish that the beetles that pollinate them respond to the infrared radiation, the authors made 3D model cones that could be controllably heated and placed them next to real cycad plants. Through clever manipulations like surrounding the heated cones with infrared-transparent plastic films to block convection, the authors showed that the beetle species that pollinates these plants uses infrared sensing to detect and navigate to the cones. They go on to identify the specialized antennae responsible for infrared sensing and then perform electrophysiological measurements, measuring increases in neural spike rates if the antennae experience heat. These sorts of measurements are technically challenging, and it’s remarkable that electrophysiology is just one panel of one figure of this paper! Then, examining the transcriptome of the antennae — i.e. what genes are being transcribed from DNA to RNA, indicating what the cells are doing — they identify a putative infrared sensor that turns out to be a known component of infrared sensing in snakes and mosquitoes. Alphafold gives the structure — a membrane channel — and further analysis follows, including comparisons with similar proteins from other, non-thermogenic-plant-pollinating beetles. Analyses of the colors of a variety of cones and flowers in many different plants, including developing “an AI platform to extract large-scale color data from community science platforms” and reconstruction of the evolutionary history of heat-generating plants, leads to the striking conclusion that thermogenesis evolved around 275 million years ago. The dominance of color as a target for pollinators occurred later, as diurnal pollinators like bees and butterflies expanded.

As mentioned, the paper is amazing, full of fascinating data and insightful analyses, and the study intersects a remarkable range of fields and topics.

There’s a lot of beautiful physics involved in the perception of visible light, including our ability to see single photons (!) and the encoding of information in membrane voltage spikes. (See e.g. Phil Nelson’s “From Photon to Neuron”.) I wondered, after reading this paper, what the underlying physical constraints are for sensing thermal (infrared) radiation and using it to navigate. For visible light, relatively energetic photons stimulate electronic transitions in molecules in photoreceptor cells. Heat plays a role, though, as thermally excited transitions (“dark noise”) provide a background level of stimulation that fundamentally constrains the sensitivity of our vision. (See for example the book by Nelson noted above, or Bill Bialek’s “Biophysics: Searching for Principles”, and references therein. Both are excellent books.)

For infrared detection the heat itself is the signal, vibrational modes in molecules throughout the insect antenna are likely excited by infrared photons. Presumably there’s some interplay between the plant’s temperature, the insect sensory neuron’s integration times, the thermal conductivity of the watery medium, and the ambient temperature that constrains the performance of thermal sensing. Searching a bit, I found — and I should have expected this — that Bill Bialek described this nearly 40 years ago (“Physical Limits to Sensation and Perception,” Annual Review of Biophysics, 16: 455-478, 1987; Link). Like the nagivation of bacteria towards chemical signals, there’s perhaps also a relationship between integration time and directional accuracy that isn’t in the paper noted above, though perhaps it’s in other articles: if the beetle integrates its stimuli for a long time the thermal discrimination is great, but it’s less likely to turn nimbly and precisely towards the plant.

Intriguingly, Valencia-Montoya and colleagues’ phylogenetic analysis implies “an evolutionary trade-off” for plants between generating heat and making colorful flowers. Do the physical mechanisms limiting the performance of each underlie this trade-off? Perhaps biophysicists out there looking for interesting problems can turn to the hot topic of plants.

Today’s illustration

In the photo above, from 2019, I’m at the South Slough Reserve, surrounded by skunk cabbage, which is common in marshy areas of Oregon. Yes, they have a skunk-like aroma. Reading a bit about thermogenesis I encountered skunk cabbage as a heat generator, and I was excited that perhaps, taking a thermal camera out at dusk, I could see them glow. Unfortunately, reading more, I learned that Symplocarpus foetidus, the skunk cabbage of the Eastern US, is thermogenic and the Western skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) is not. On the plus side, the eastern skunk cabbage smells worse and has a hideous splotchy red bloom; ours has a mild smell and is a beautiful yellow.

I painted today’s illustration from a photo I took.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. January 13, 2026

So, what you are saying is I should go out this spring into the Michigan woods with an infrared camera and hunt for skunk cabbage.

Yes! There’s probably a specific time of day that they turn on, maybe dusk if they’re like the cycads in the paper. I think it would be a fun expedition!