About a recent paper on biological light emission. Do you emit light? The naive answer is no. None of us light up a room as we enter, other than perhaps metaphorically. The intermediate level answer, familiar to undergraduate physics majors, is yes — not by virtue of being alive but because of fundamental thermodynamics: everything emits electromagnetic radiation (light), the amount increasing strongly with temperature. The Sun (temperature approximately 6,000 ° C) emits much more light than you (37° C). Your emitted light is mostly in infrared wavelengths, detectable by night vision goggles; its visible component is far too weak for you to see.

Until a few months ago, my knowledge ended there. Then I came across a preprint, “Imaging Ultraweak Photon Emission from Living and Dead Mice and from Plants under Stress” (V. Salari et al., bioRxiv, 2024); link), about investigating a different sort of light emission that seems intrinsic to living things. The authors didn’t discover this “ultraweak photon emission” (UPE) — apparently it has been noticed for decades, sometimes under the name biophoton emission. A fascinating review paper from 2024 (R. R. Mould et al., Front. Physiol. 15, 2024; link) notes odd, controversial studies dating from the 1920s. The phenomenon has been minimally investigated and its physical origins are unclear. It is hypothesized that the visible-range light emission is a byproduct of energetic reactions generating reactive oxygen species, which are produced during mitochondrial respiration, photosynthesis, and other energy transduction processes, with excited oxygen atoms emitting photons as they relax to lower energy states. Like the name implies, UPE is weak, at most one hundred photons per square centimeter per second, necessitating sensitive cameras and long exposures for detection. Nonetheless, this “biophoton” emission is claimed to be far stronger than thermal (blackbody) radiation from a room-temperature object, which is less than 10-6 visible-wavelength photons/cm2/s.

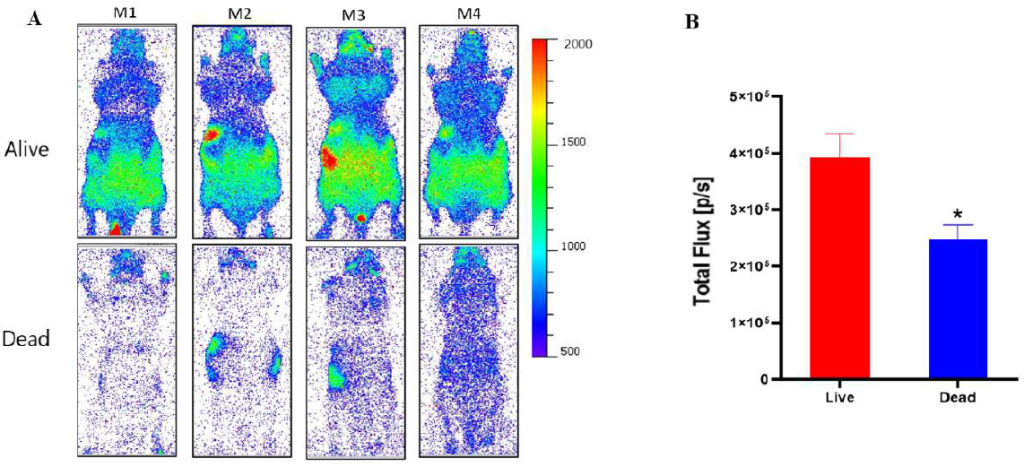

In the Salari et al. study, the authors collected light for 60 minutes from live mice, killed the mice, waited half an hour, and continued to image, keeping the temperature constant. The mice emitted about 1.5 times more light when alive than when dead. The authors also looked at plants, subjecting them to various stresses injuries, finding light emission up to about 10 times higher than from unstressed plants.

One can imagine, as the authors note, that UPE might serve as a diagnostic for cells, tissues, or even whole organisms. Measuring light emission is, after all, non-invasive. Perhaps there are emission signatures of, for example, abnormal respiration — something that can be challenging to measure.

I’m amazed that I never before heard of ultraweak photon emission (or the more sensible name, biophoton emission), and lots of questions came to mind. What’s the spectrum of the light emission? From the above-mentioned review article (Mould et al. 2024), “fully resolved spectra of UPE have never been acquired,” due to the low light intensities. The review article has a good discussion of measurement challenges and potential applications. I’m curious how this light emission varies across organisms or organs within an organism, both to learn about different systems but also to find one that might be a good model to study the phenomenon itself. I find it odd that the Salari et al. paper looked at mice — they’re of course quite opaque, so presumably the vast majority of photons generated during cellular activities are absorbed within the mouse itself.

I also wonder whether any organisms, especially slow movers or their prey, detect and make use of biophoton emission. The review paper notes that investigation of UPE began by wondering about potential non-chemical means of cell-cell communication! I admit to not having looked into the existing literature on the topic besides the two papers mentioned here, but I will nonetheless predict that there are many unanswered (and unasked) questions. Maybe light emission will someday end up in some revised edition of my book; so far the only biology-related photons are in a brief mention of luciferase in the context of DNA sequencing (see also here).

Today’s illustration

A beech marten. I recently read My Stupid Intentions by Bernardo Zannoni, an excellent novel narrated by one of these animals, so thought I’d paint it. I don’t know how much light it emits. (Source photo: https://www.sciencephoto.com/media/550668/view/beech-marten-on-a-branch)

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. March 4, 2025