About a recent paper from my lab: Julia S Ngo, Piyush Amitabh, Jonah G Sokoloff, Calvin Trinh, Travis J Wiles, Karen Guillemin, and Raghuveer Parthasarathy, “The Vibrio Type VI Secretion System Induces Intestinal Macrophage Redistribution and Enhanced Intestinal Motility,” mBio, (2024).

A few years ago, my lab discovered that Vibrio cholerae, the bacteria that cause cholera, can induce strong gut contractions, about 100% stronger than normal [paper; blog post]. This completely unexpected finding was in zebrafish larvae, but we suspect something similar would occur in humans. Required for this intestinal stimulation is a syringe-like stabbing apparatus called the Type VI Secretion System (T6SS) wielded by Vibrio cholerae and other bacterial species. What’s the connection between bacterial stabbing and gut contractions? This has puzzled us for years.

We suspected that immune cells may be involved. In part, this was because our own work had shown that a different Vibrio, one native to zebrafish, stimulates the immune system. In part, this was because recent work by other labs had shown that macrophages, a type of immune cell, communicate with the enteric neurons that line the gut, and that reducing the number of macrophages leads to faster transport of gut contents. To investigate links between bacteria, immune cells, and gut mechanics, we embarked on a long series of experiments, working with the above-mentioned zebrafish-native Vibrio. “We” is mainly Julia Ngo, a talented graduate student. Julia engineered this Vibrio so that its T6SS syringe lacks its actin crosslinking domain. Without this component, the bacteria should be able to stab and kill other bacteria, which we verified, but would be powerless against eukaryotic cells, like those of a zebrafish.

In fish colonized by unmodified Vibrio, Julia found that the zebrafish gut is buffetted by strong contractions, at their normal frequency but with roughly 100% greater in amplitude, with no change in frequency (upper movie), just like we saw with Vibrio cholerae. In fish colonized by Vibrio that lack the actin crosslinking domain, there are the normal-strength periodic, propagating contractions (lower movie).

Next, we applied clever CRISPR-based methods developed by other labs to reduce the number of macrophages in zebrafish, disabling a transcription factor involved in macrophage development. The mutant fish had about half the number of macrophages as normal fish, and their gut contractions were about 100% stronger with no change in frequency. The observation is consistent with the picture that macrophages down-regulate the gut stimulatory activity of the enteric neurons; with fewer macrophages, the neurons are less constrained.

Adding Vibrio to these macrophage-depleted fish had no effect on gut contractions, with or without the actin crosslinking domain, implying that the path connecting bacteria and intestinal mechanics goes through the immune cells.

We suspected, given these observations, that Vibrio may be killing macrophages — it’s known that they can do so when pitted against each other in a petri dish — but we never found any notable sign of dead macrophages. There were plenty of dead cells, however, when the wild-type Vibrio (with an intact T6SS) was present, and these dead cells were mainly located at the posterior “vent” of the zebrafish gut. Vibrio induced a lot of posterior tissue damage.

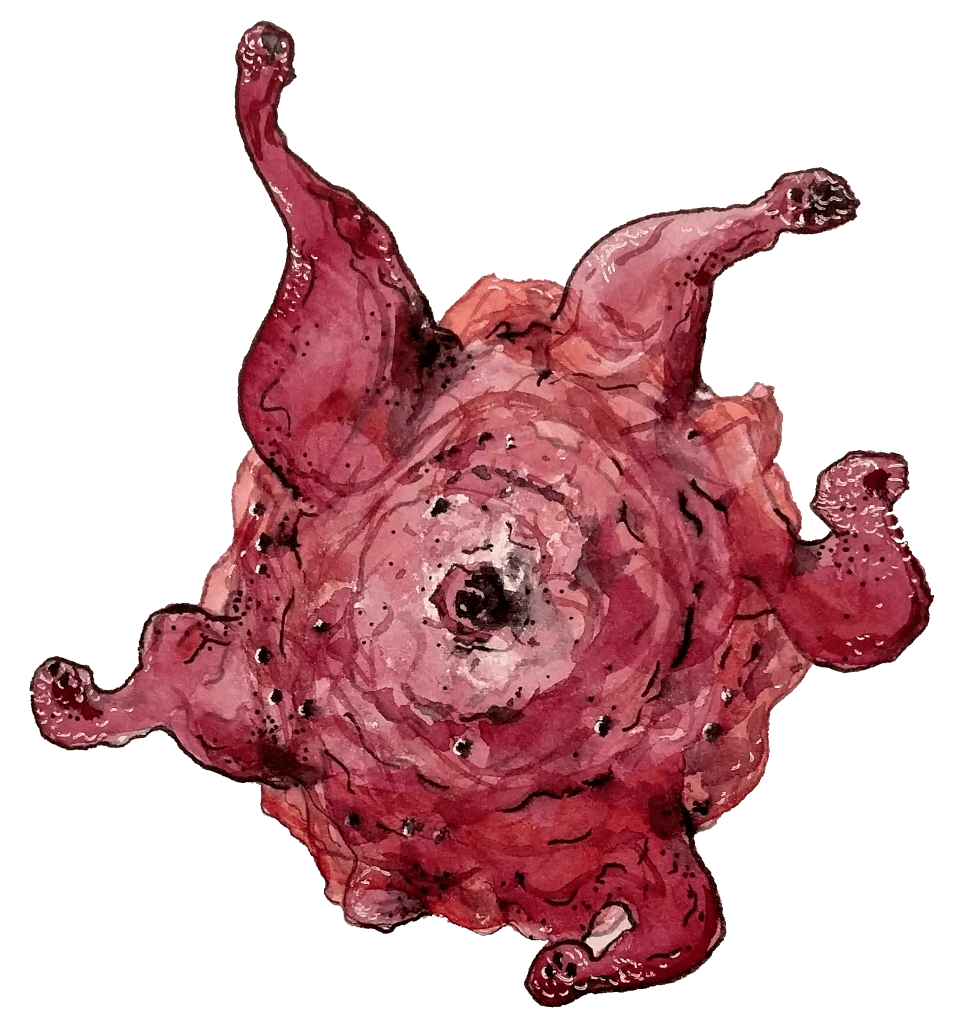

We then more carefully watched the macrophages, applying our favorite technique of light sheet fluorescence microscopy to image the entire zebrafish gut, in 3D, over many hours. One of my favorite images — actually just a quarter of the full extent of scan — is this one, one of many expertly taken by graduate student Piyush Amitabh:

Here we see macrophages in magenta and cells expressing the tnfa gene, an indicator of immune stimulation, in cyan. The latter include many cell types: macrophages, other immune cells, neurons, and beautiful rosettes surrounding sensory organs lining the fish body. The macrophages move and, if Vibrio with the normal, functional T6SS is present, many of them migrate over several hours to the posterior end of the gut, where the tissue damage has occurred. Macrophage numbers in the midgut, where the immune cells would normally sit in close proximity to enteric neurons, are depleted. And so, because of the redistribution of the macrophages, we’re left with a similar situation as seen in mutant fish with few macrophages: enteric neurons, freed of downregulation by the immune cells, stimulate strong gut contractions.

While this is, we think, a plausible and parsimonious explanation of how bacterial T6SS activity leads to strong gut contractions, it is not a proof. We can’t, with our current methods, see the enteric neural activity or directly observe or perturb the macrophage-neuron communication. Still, I think it’s a significant step forward, especially given that just a few years ago neither we nor anyone else had any idea that bacteria and intestinal mechanics were linked at all.

I also find our conclusion satisfying from a biophysical perspective. It could have been that the connection between bacteria and gut contractions was some specific biochemical interaction, driven perhaps by some secreted molecule. Instead, we need not invoke any new signals, but rather it’s the spatial rearrangement of the players that changes the overall behavior. What’s more, its an outcome that makes sense: the gut is damaged; macrophages migrate to the wound (as they always do), leaving their normal location. That departure itself is the trigger for the gut to push harder, perhaps driving out the cause of its misfortune.

Today’s illustration

A macrophage.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy; November 29, 2024