I’m always interested to hear who won the latest Physics Nobel Prize, and today’s announcement was particularly exciting: John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.” Is it surprising? Is it controversial? Apparently yes. I predicted Hopfield in response to a friend’s poll a few weeks ago, though I admit it was in part wishful thinking — his work is amazing, and in a sense a prize for Hopfield is a prize for biophysics, helping advance awareness of the field and its wonders. I’ll explain the tenuous biophysical connection shortly, but first the more standard summary.

Hopfield and Hinton won the Nobel for theoretical work that underpins modern machine learning, especially involving neural networks. The impact of machine learning hardly needs elaboration in 2024. In computer vision alone, the immense leaps we’ve witnessed over the past decade in computers’ ability to recognize objects and even generate new, realistic images are stunning. Machine learning methods are largely based on neural networks, computational structures inspired (in a vague sense) by biological neural organization. In a neural network, neurons (so to speak) perform mathematical operations on subsets of input data or on the outputs of other neurons, and the parameters of these operations are themselves learned from data. A neuron in the network may, for example, output (3 x the intensity of pixel 1) + (4.2 x the intensity of pixel 17) + (-6.7 x the intensity of pixel 38), with “3”, “4.2”, and “-6.7” leaned from operating on other datasets whose correct output is known.

Can such a structure lead to stable parameter values? Can it learn? Hopfield’s and then Hinton’s work in the 1980s, on a simple type of neural network, showed that the answer is “yes.” (Some more insights are available from the Nobel committee’s “advanced information” document.)

But is it Physics?

All this sounds nice for computer science, or for building language translators or self-driving cars, but is it Physics? I’d argue the answer is “yes.” These ideas of network properties, stability, and transitions didn’t spring up de novo, but emerged via classic problems in statistical mechanics, one of the fundamental, core areas of physics. Hopfield’s model was, in fact, a “spin glass” model, originally developed to describe magnetic materials and phase transitions. Spin glasses are interesting — I used to work on them long ago — but if the utility of spin glasses were simply spin glasses, hardly anyone would care. The beauty of physics lies in large part in the universality of its concepts: the insights from a spin glass model can apply to magnets, or protein folding, or machine learning. This is a strength of physics, not a limitation, and it should be acknowledged as such.

The intersection of statistical mechanics and computer science continues to develop in fascinating ways. Why neural networks work so well, how their properties scale with size, and how to interpret them remain open questions, and questions in which approaches from physics are proving useful. (Working at this intersection is a good way to make yourself highly appealing in the job market, by the way.)

Unfortunately, I don’t think the Nobel committee’s announcement information makes the “this is physics” case as well as it should, focusing on impact and applications instead of the intellectual history of the ideas. Impact and applications are important, but the story is deeper than this. Especially for students wondering what to study, understanding where ideas come from is important. If you want to make breakthroughs in artificial intelligence, should you necessarily study artificial intelligence?

The prize would have been even better if…

Consider a totally different puzzle: How can your cells do such a great job assembling proteins, hardly ever making mistakes? To a traditionally trained biologist, this may not seem a question worth asking; protein synthesis is what it is. Physics — statistical mechanics, in fact — reveals the mystery. A protein is a chain of amino acids, each added one by one as the molecule is assembled. There are many choices of amino acid. The correct one, fitting the template ultimately provided by the cell’s genetic code, has the lowest “free energy” when bound. Any incorrect amino acid has a higher free energy. (Technically, it’s the binding of the tRNA that I should be referring to, but that’s an irrelevant complication; the argument is the same.) From undergraduate statistical mechanics we know that at equilibrium, the probability of having the wrong amino acid relative to the correct one is a simple function of the free energy difference and the temperature. One can calculate, since we know these free energies and temperature, what this probability is, i.e. the error rate for adding amino acids: it’s about 0.1, or 1 in 10. The actual error rate: About 1 in 10000 — a thousand times lower! How can this be?

Remarkably, one can get around this thermodynamically determined error rate by supplying energy to introduce one or more irreversible steps to the process. Then, the overall error rate is determined not just by the free energy differences but also by the kinetics, or rates, of the amino acids binding to or unbinding from their targets. The error rate can be suppressed, roughly, by the ratio of the unbinding rates of the incorrect and correct amino acids, a ratio that wouldn’t matter at all in equilibrium. That ratio may be quite large — enough to give a vital thousand-fold improvement in the accuracy of forming the intended protein molecule.

This clever scheme for error suppression actually occurs in cells, not just for protein synthesis but in several other contexts. It’s called kinetic proofreading. It was proposed in 1974 by… John Hopfield! (In 1975, Jacques Ninio independently came up with the same idea.)

If I were the Nobel committee I would have lumped kinetic proofreading together with neural networks and given the majority of the prize to Hopfield, for more general contributions to connecting physics to information processing, whether biological or computational. As an added bonus, it would be a more biophysical prize! Nonetheless, I’m happy with the prize as it is.

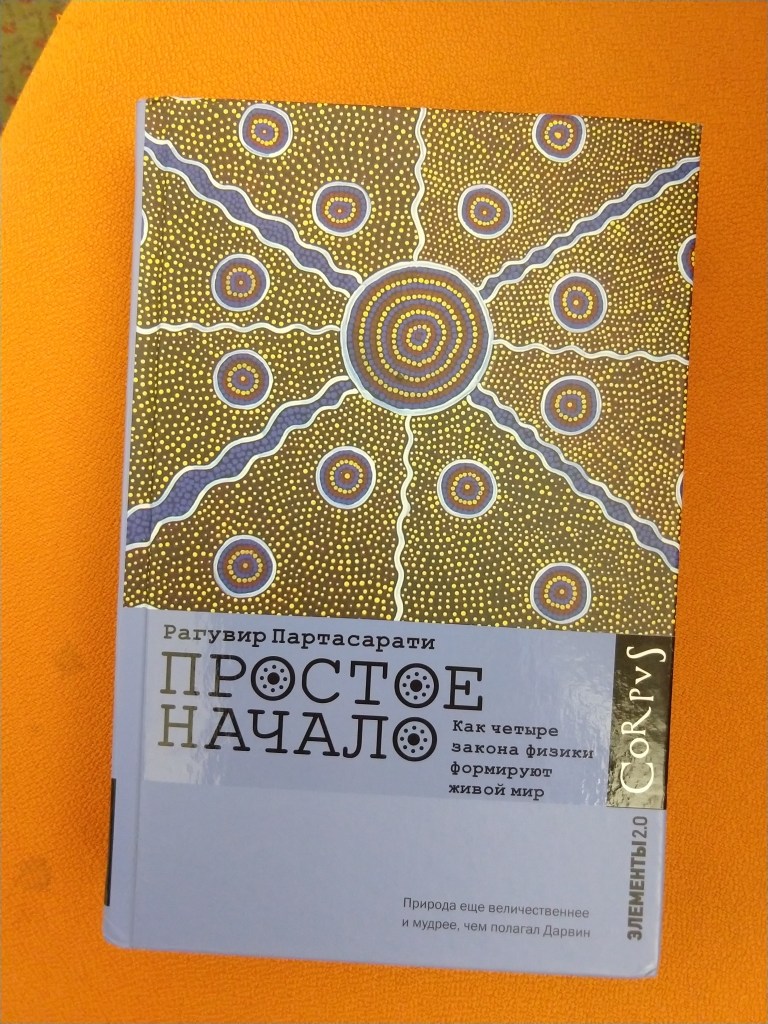

I’ll end with a far less important biophysical note: the Russian translation of my pop-science biophysics book is out! I don’t recommend bypassing trade embargoes, but if you can’t live without a copy, you can buy it through a German bookseller. Perhaps via Kyrgyzstan…

Today’s illustration

A watercolor based on a photo I took a few weeks ago of an Italian soda. I wanted to again paint a liquid-filled glass with light shining through it (as in the illustration a few posts ago). I spent much less time on this one, and not surprisingly it didn’t turn out as well, but it was enjoyable to paint.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. October 8, 2024