You will find this post either shocking or obvious. If it’s obvious, you may nonetheless be shocked that others don’t find it obvious, or by how quickly the situation it describes has gone from shocking to obvious.

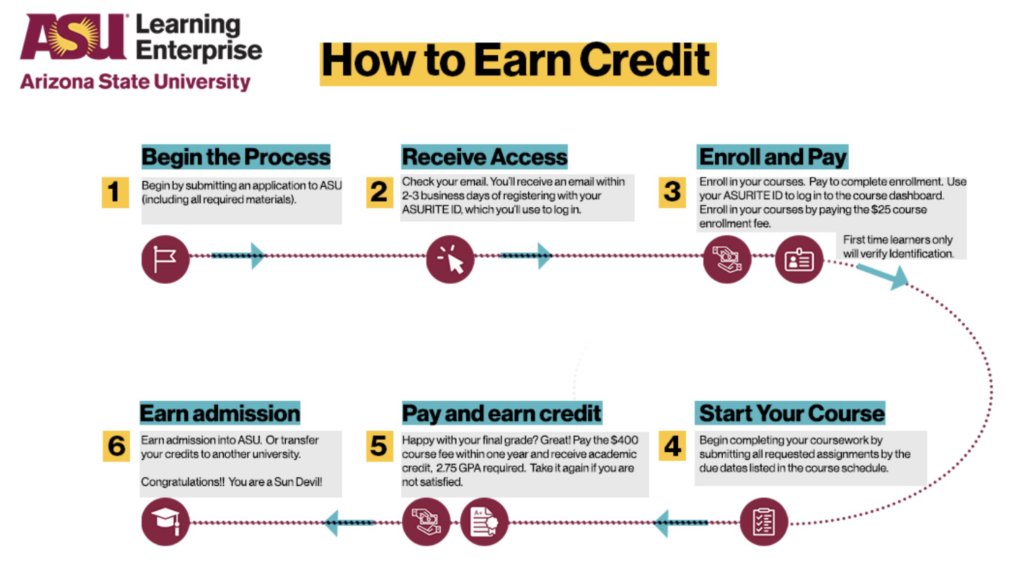

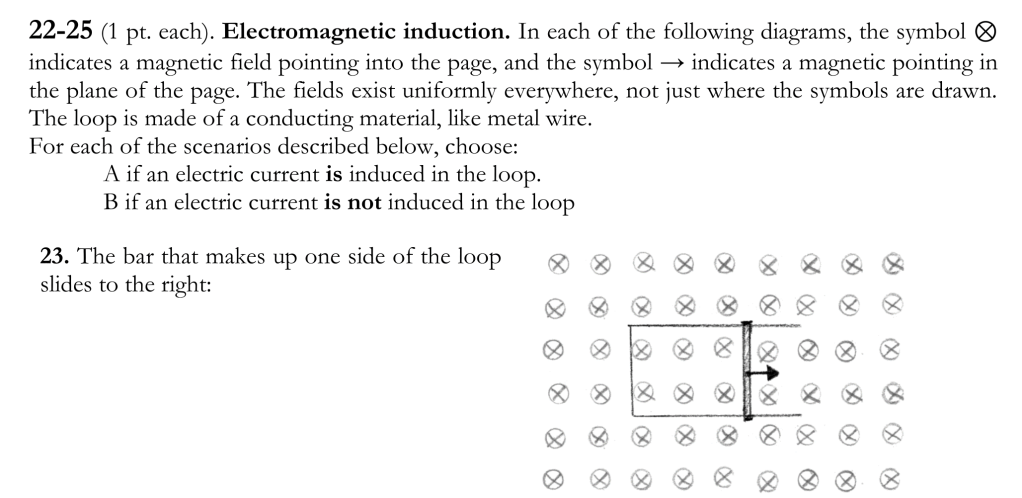

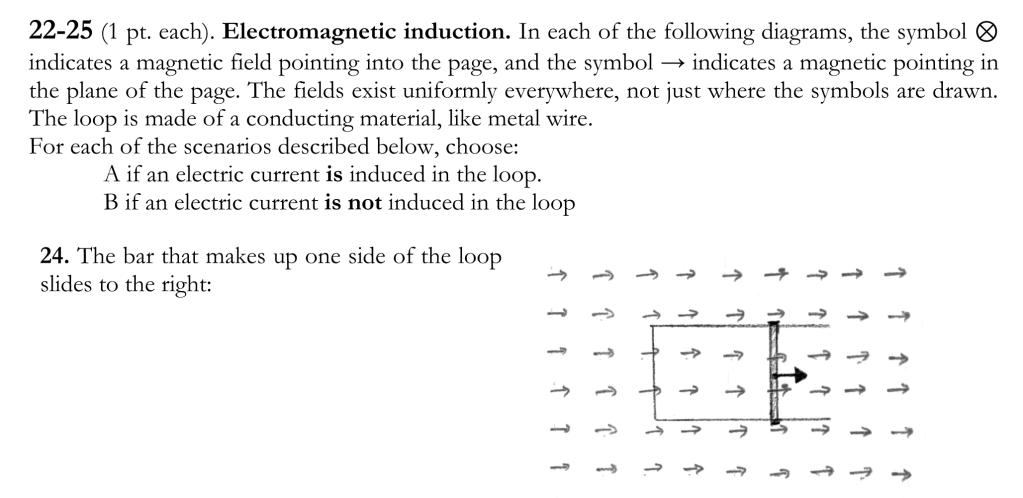

The topic is AI (artificial intelligence) and teaching, which I will illustrate with an example. Below are a few related questions from the midterm exam I gave a few weeks ago in my Physics of Solar and Renewable Energies course. Don’t worry if you don’t know anything about electromagnetism and electricity generation — the point is that the questions involve my crude schematic drawings and conceptual understanding. (Click the arrows to advance.)

Can current AI models (May 2024) answer these questions? Yes. Perfectly. What’s more, the format for delivering these questions to the AI instrument is simply to upload a PDF of the entire exam and ask, “Choose the correct answer for each question from 2 through 27. Give explanations of the reasoning for each.” (The full prompt is below [1].) Within seconds, I got answers to every question on the exam, with explanations, for both multiple choice and short answer questions. The AI in this case is Claude 3 Sonnet, the free version of Anthropic’s Claude. The answers are not perfect, but they’re considerably better than those of the median student. Claude 3, if it were a student, would have gotten the 18th highest score out of 97 students (14th of 97 on the multiple choice questions alone).

If you’ve been keeping up with contemporary AI, you’re not surprised. But you should be surprised by the following: There are people teaching lower level college courses in 2024 who still give online exams. If the aim of an assessment is to assess understanding, this is clearly hopeless. One might disagree, arguing that all students are scrupulously honest. I could perhaps accept this for upper-level classes, or small classes, but not for large, lower-level classes. You don’t have to take my word for it: you can ask students themselves, paying attention especially to the frustration of the dedicated students. Or, if you really think there wouldn’t be a sizeable fraction of students asking AI for online exam answers, you should give students along with their exam a PDF of the solutions with the request not to open it. Since opening the PDF takes the same amount of effort as uploading the PDF to a free AI tool, as illustrated above, one should be just as willing to give the solutions PDF as to give the online exam.

One can argue that we shouldn’t care; students who cheat are cheating themselves from gaining understanding and so will face consequences later, so justice will be served. True, I suppose, as we’re finding for example that doctors’ exam scores correlate with patient survival, implying that a lack of skills resulting from dishonesty will similarly correlate with real-world harm, but it seems a slow and painful way to handle educational integrity! Less dramatically, we then face these unprepared students in later courses, which makes instructor and student alike miserable. (That’s why courses have prerequisites.)

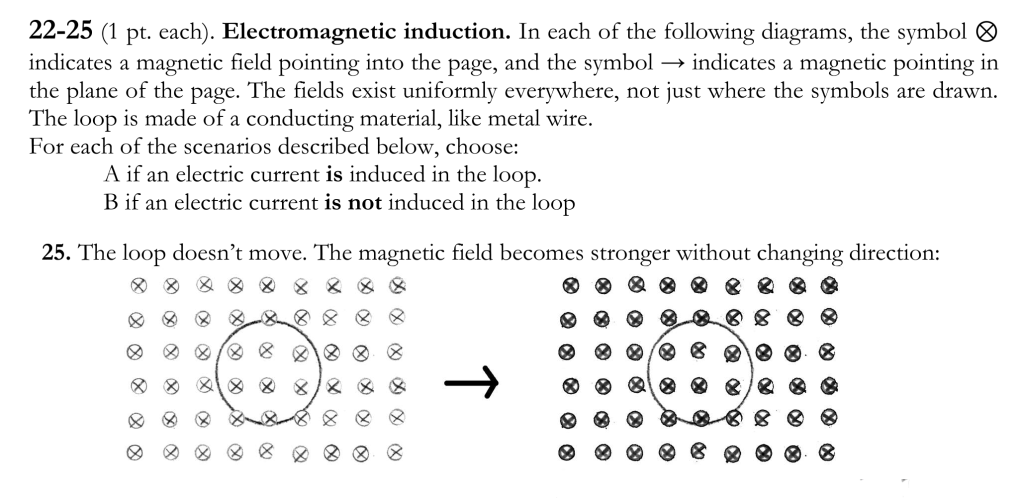

Universities, including my own, struggle with what to do about AI and education, a combination that promises wonderful routes to learning along with serious ethical difficulties. AI is currently the topic of several weeks of our science teaching journal club this term whose attendees, all very thoughtful about pedagogy, point out that in-person assessments are now the only sensible path. I agree, though I struggle with the consequences. Arizona State University, for example, is making online courses for college credit open to anyone, a potentially transformative path for motivated high school students. This could be phenomenal for a lot of people. But: can one have confidence in grades from these courses?

Would you support a policy of prohibiting on-line assessments at your school?

Today’s illustration

An eagle owl, based on a few different photos.

— Raghuveer Parthasarathy. May 22, 2024

Notes

[1] The exam consisted of multiple choice and short answer questions, separated by some survey questions. I asked Claude 3 to consider each piece separately. The multiple choice prompt was, “In the attached PDF document, questions start on page 2. Questions 2 through 27 are multiple choice questions. Choose the correct answer for each question from 2 through 27. Give explanations of the reasoning for each.” The short answer prompt was, “Now give answers to the “short answer” questions 32-35.” I also asked for its survey question reponses.

Typically bad grades aren’t a hopeful sign. However being the sole TA for an undergraduate online chemistry course, we had course averages that would indicate the cheating issue isn’t too widespread, or they’re just bad at cheating. We didn’t employ any sort of proctoring with the logic being that if they cheat now it will only hurt them later. I guess this is maybe hopeful for the future, or just a lack of adoption.

I hadn’t sufficiently appreciated the corollary to “cheating will only hurt the cheaters later,” which is of course “cheating will hurt the cheater’s clients later!” So thanks for that.

A few thoughts:

All good points. I definitely agree with #3! This should be a major priority, and I know you’re working on methods / tools that can make it successful — thanks!

About #2: I increasingly feel that rather than the university providing more support, and (as a result) increasing the cost of tuition to pay for it, we should move back to a model in which tuition was far lower, leading to lower burdens on students across the board. But that’s another story…

Problem: Teachers can no longer ask questions of students that machines can’t answer.

Solution: Restrict students to in-person assessments with pencil and paper or oral assessments. (Impractical for large classes.) Appropriately 10% of my students attempted various forms of cheating, even when proctored.

Question: What skills/Knowledge do students need to fill the narrowing gap between what machines can do and what the world needs done?

Observation 1: Few can compete effectively in the machine domain. And they are not actually competing; they are augmenting the power and scope of the machine domain, further narrowing the machine-world gap.

Observation 2: Schools have become financial institutions with sports franchises, rather than educational institutions. Online courses provide a higher return on investment (ROI) and cast a wider student net than any physical classroom or laboratory. Students want the highest grade per dollar invested. This perverse alignment has produced an academic race to the bottom.